Coding for analysis

I have come back to this topic since I am now actively coding the interviews and digital artifacts for this research. I am reading and reflecting on my coding practices since this is an essential element of the work and will lead to effective and reliable analysis of the lived experiences of the participants being interviewed. While I understand the underlying process – the ‘how to’ of coding – I don’t fully understand the what, when, and why of coding. I’ve gone back to some of the resources and reference materials that can inform and support as I go deeper into the research and journalling.

Here is the short list of my references:

Agar, M. (2011). Making sense of one other for another: Ethnography as translation. Language & Communication, 31(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2010.05.001

Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes (2nd Edition). The University of Chicago Press.

Jackson, K., & Bazeley, P. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

Agar suggests using symbolic coding to capture where emphasis is placed in phonological prominence, length of pauses, non verbal interruptions and overlaps, and intonation when delivering sentences or ideas. These symbols include

- + indicating a brief pause of less than one second;

- (3.4) referencing approximate length of a pause;

- – indicating a rise in intonation;

- = indicates a run on without pause;

- italics in the transcript indicates “phonological prominence, whether due to stress, volume, pitch, or some combination” (p. 214).

Since this information was published by Agar before the prominence of video recording and web-based interview methodology, with a specific application to audio transcriptions done within a physical location for ethnographic research, this has some potential for application to video recordings. I wonder if this is a good way to code some of the non-verbal elements of the interviews. If this type of coding is done, will it inform the results in some significant way? This is worthy of more reflection and consideration when I get to the deep analysis work coming up after the interviews are completed.

In a chapter on processing field notes from ethnographic research, Emerson et al., (2011) outline some considerations for coding and memoing. These authors suggest asking questions that “develop, identify, elaborate, and refine analytic categories and insights” (p. 175). While the use of computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) is suggested as being beneficial, it is the researcher who “creates, changes, and reconceptualizes interpretations and analyses” (p. 177). Researchers should rely on their experiences relating to the research topics and concepts, bring in various resources as needed, relating to other elements already experienced in the research, insights gained from other contexts, or orientations obtained from different fields of study. Emerson et al., suggest that “nothing is out of bounds” (p. 177). For my research, this means that I should extend and expand my coding to bring in more of these connections as I work through the transcripts and artifacts. These authors suggest several questions that can help me refocus and revise my coding practice:

- What are people doing? What are they trying to accomplish?

- What specific means and/or strategies do they use?

- How do they talk about, characterize, and understand what is going on?

- What assumptions are they making?

- What do I see going on? What did I learn from this?

- How is what is going on here similar to or different from other incidents or events?

- What is a broader significance of this incident or event? (p. 177)

One of the questions I’m facing, now that four interviews have been coded, is if I should go back to the first two interviews and recode based on some of the new codes I’ve added from the third and fourth interview. If I follow the advice from Emerson et al., that nothing is out of bounds, then I should go back and re-code. Jackson and Bazeley suggest coding and uncoding using the coding stripes available in NVivo. One thing I will do before I review or re-examine codes in previous interviews, is to make sure I have attached a colour to each of the codes – not that these colours are specifically significant, they do allow me to see the length of the section that has been coded with that particular term/code.

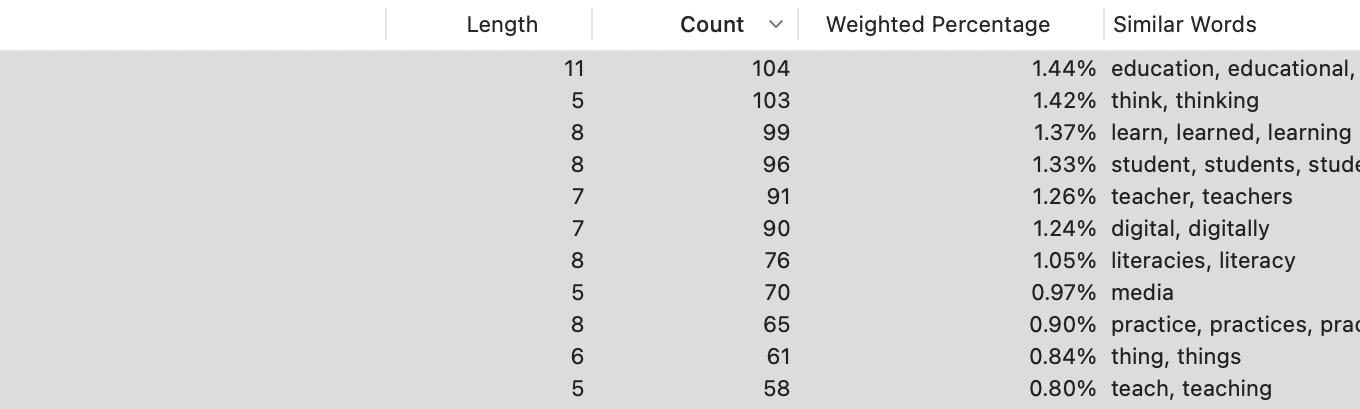

Of greatest value to my coding work at this point is a reminder by Saldaña (2016) to look for patterns since these will identify “habits, salience, and importance in people’s daily lives” with a focus on the 5 R’s – “routines, rituals, rules, roles, and relationships” (p. 6). Saldaña reminds me that coding is fluid and cyclic, not just labelling, but linking – summation and complication. Saldaña references Charmaz (2014) who uses the metaphor of bones and skeleton to reference coding and analysis (bones) and integration of research themes (skeleton). I will heed Saldaña’s caution to not jump to themes and categories too quickly. As I look at coding elements in quality (how often they are used) or quantity (between 50-300 different codes), I also need to keep in mind the suggestions in Saldaña for the total number of themes and concepts emerging from the coding (see page 25).

The value and insight from Saldaña that does add to my coding considerations is the advice to items in the codebook should contain a short description, a detailed description, inclusion or exclusion criteria, typical and atypical examplars, and a ‘close, but no’ type of code that outlines data that might be mistaken as something else.