2.2.3 Literacies

Defining Literacy

Literacy is a human process of making sense of our world, binding our understanding and relationships to each other and our contexts. Literacy is found in the “relationship between human practices and the production, distribution, exchange, refinement, negotiation and contestation of meaning” (Lankshear & Knobel, 2007, p. 2). Within this process there is a reciprocity between practice and meaning-making, between context and language, and between reading and writing (Lankshear & Knobel, 2007).

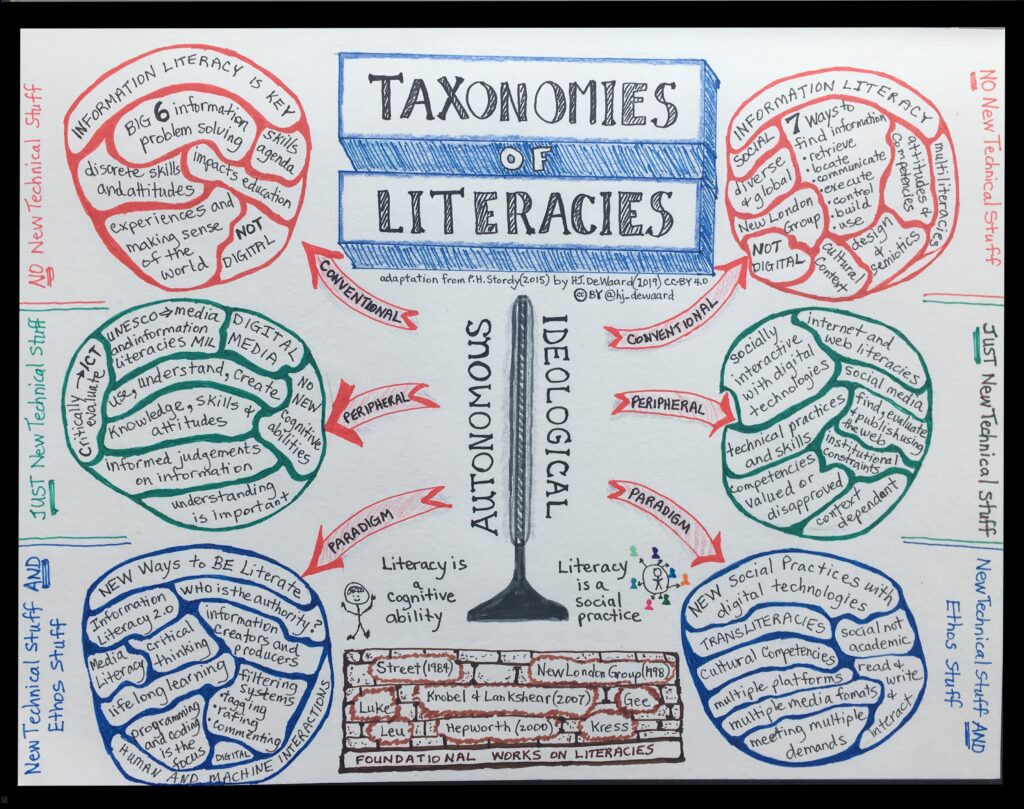

Stordy (2015) examines literacy/ literacies to create a taxonomy that encompasses a multitude of definitions and variations of relevant terms. This taxonomy includes both an autonomous perspective outlining psychological cognitive definitions and an ideological perspective relating to socio-cultural approaches that define literacy/literacies. Stordy (2015) differentiates these into those literacies that integrate no-or-few digital technologies (conventional), those that incorporate new technical elements (peripheral), and those literacies that assimilate new technical stuff with new ‘ethos stuff’ (paradigm), further described in the Taxonomy of Literacies image (see Figure 5).

The taxonomy is grounded in literacy research and provides a working definition of literacies that “captures the complementary nature of literacy as a cognitive ability and a social practice” (Stordy, 2015, p. 472). While Stordy (2015) acknowledges the challenges and limitations of this framework, and recognizes that the borders between these concepts are fuzzy and permeable, this taxonomy supports the reframing of literacies in a way that clarifies understanding.

Literacy terminology is frequently confused with notions of skills, fluency and competency but for this research, these should be regarded as different conceptions. Fluencies is the ability to speak, read, and write in a given language quickly and easily, while competency is defined by having skills and abilities to do a job (“Competency,” OED Online; “Fluency,” OED Online). These definitions are not the same thing, but can be considered to be subsumed within the broader term literacy. This clarification is made here since research applies these terms interchangeably, yet they are distinctly different conceptions.

Defining Media Literacy

Media literacy, from an autonomous stance, is defined as the ability to access, analyze, use, create, and evaluate information using a variety of communication formats (Baker, 2016; Hobbs, 2019; Rogow, 2019). The process of critical inquiry and reflection are central to being media literate (Grizzle et al., 2013) since “media literate people apply their skills to all symbol-based communication, irrespective of message” (Rogow, 2019, p. 122). These messages are bound by the types of media texts (print, visual, audio, digital) used to create and communicate (Baker, 2016; Hobbs, 2017). Media literacy involves examining the semiotics and symbolism of text messages as part of a meaning-making inquiry (Gee, 2015).

From an ideological stance, media literacy shifts beyond encoding and decoding media texts to engage in meaning making within socially, politically, and culturally contextualized media consumption and production spaces (Baker, 2016; Hobbs, 2017; Hoechsmann, 2019; Hoechsmann & Poyntz, 2012). Media literacy is a process of becoming (Gee, 2017), networked (Ito et al., 2010; West-Puckett et al., 2018) participatory (Jenkins et al., 2009), discursive (Gee, 2015), and complicated (boyd, 2010). Within teacher education, these media literacy processes should be evident in the MDL that occurs with the OEPr of teacher educators.

UNESCO combines media and information literacies (MIL) into a singular concept that encompasses and subsumes other literacies such as computer, internet, digital, library, news, media and information literacies. This MIL framework outlines five laws of MIL (Grizzle & Singh, n.d.) that are presented in a matrix with three components (access, evaluate, create) and includes competencies and performance indicators that can be applied to individual teachers and FoE at the organizational level.

Defining Digital Literacy

Stordy (2015) defines digital literacies as the “abilities a person or social group draws upon when interacting with digital technologies to derive or produce meaning, and the social, learning and work-related practices that these abilities are applied to” (p. 472). When considering digital literacies as autonomous, conceptions relate to skills, proficiencies, fluencies, and competencies. Competencies broadly cover knowledge, skills, attitudes and values (OECD, 2018). Skills and fluencies focus on the mechanics of how to use digital technologies, and knowledge relates to the information required and used when manipulating digital resources. Competencies subsume skills, fluencies and knowledge into a fuller conception that includes attitudes and values (Spante et al., 2018). Competencies and literacies are frequently interchanged in the literature, depending on geographic contexts (Spante et al., 2018). Accordingly, some research suggests that digital literacy originated from a “skill-based understanding of the concept and thus relates to the functional use of technology and skills adaptation” (Spante et al., 2018, p. 7).

Ideologically, digital literacy is a “complex and socio-culturally sensitive issue” (Lemos & Nascimbeni, 2016, p. 2). Digital literacy shifts into social, collaborative, communication and sense-making actions and interactions using a variety of digital devices (Beetham et al., 2012; Belshaw, 2012; Lemos & Nascimbeni, 2016). Digital literacy is therefore defined as a dynamic process wherein the “creative use of diverse digital devices to achieve goals related to work, employability, learning, leisure, inclusion and/or participation in society” (Lemos & Nascimbeni, 2016, p. 2) are integrated into everyday life (Belshaw, 2012). Digital behaviors, practices, identities and citizenship, as well as wellbeing, are incorporated into this definition (Belshaw, 2012; Hoechsmann & DeWaard, 2015; Lankshear & Knobel, 2007; Spante et al., 2018).

The term critical literacy refers to the use of print and other media technologies to “analyze, critique and transform the norms, rule systems and practices governing the social fields of everyday life” (Luke, 2012, p. 5). Critical digital literacies (CDL) acknowledge power differentials, strive for equitable access to diverse resources, and the reconstruction of transformative potentials (Spante et al., 2018). This definition requires that those within a field of study examine how, why, and where norms, rules, ways of doing, ways of being in relationship to topics, processes, procedures, and each other, are critiqued with a social justice view, examining the spaces and places where those who are marginalized and disenfranchised can find intentionally equitable hospitality (Bali et al., 2019). Luke (2012) further explores how literacy in education utilizes “community study, and the analysis of social movements, service learning, and political activism, …. popular cultural texts including advertising, news, broadcast media, and the Internet” (p. 7). CDL are important considerations in course development and the design of learning experiences when infusing MDL into methods and core course requirements in teacher education programs.

The overarching conception of digital citizenship subsumes all layers of skills, fluencies, competencies, literacies, and criticality when using, creating, and communicating with digital technologies and resources (Choi et al., 2018; Hoechsmann & DeWaard, 2015). Additionally, citizenship infers activism, engagement, and cosmopolitanism (Zaidi & Rowsell, 2017). Belshaw (2012) posits nine C’s of digital literacy, identified as curation, confidence, creativity, criticality, civics, communication, construction, and cultural. These incorporate key citizenship elements. When focusing on digital citizenship and the responsible use of technology, Ribble (2017) proposes nine elements categorized under three principles of behaviour – respect, educate and protect. Although citizenship is a worthy area of investigation and needs to be recognized for future attention, it is beyond the scope of this proposed research.

Definitions and practices of critical MDL are continually in flux, since contexts dictate the core and critical elements. In teacher education programs, MDL is shaped by, and adapts to, current cultural, social, political, and technological climates.

Literacies: Untangling a Concept

Surrounding these definitions of media and digital literacies there exists a veritable Pandora’s box of literacy terminology (Belshaw, 2012) including transliteracies (Sukovic, 2016), cosmopolitan literacy (Zaidi & Rowsell, 2017), cultural literacies (Halbert & Chigeza, 2015), place based literacies (Harwood & Collier, 2017; Mills & Comber, 2013); artefactual literacies (Pahl & Rowsell, 2011); information communication literacies (Forkosh-Baruch & Avidov-Ungar, 2019; Horton, 2008); internet or web literacies; technological literacy; multiliteracies (The New London Group, 1996); multimodal; multicultural; visual literacy (Collier, 2018), transmedia literacies (Jenkins, 2010), re/mix literacies (Hoechsmann, 2019), and living literacies (Pahl et al., 2020). While this literature review does not specifically examine this tangle of terminologies, they are mentioned here to acknowledge the confusion and recognize potential misconceptions resulting from the conflation of terminology (Belshaw, 2012; Spante et al., 2018).

My research is influenced by Allen Luke’s conception of critical literacies, as literacies are described as “historical works in progress. There is no correct or universal model. Critical literacy entails a process of naming and renaming the world, seeing its patterns, designs, and complexities, and developing the capacity to redesign and reshape it” (Luke, 2012, p. 9). This conception of critical literacy rings true for my research since I wonder how TEds use and apply their contingent attitudes and technologies since their MDL and OEPr “depends upon students’ and teachers’ everyday relations of power, their lived problems and struggles, and … on educators’ professional ingenuity in navigating the enabling and disenabling local contexts of policy” (Luke, 2012, p. 9).

This research is further influenced by the conception of living literacies posited by Pahl et al. (2020) since “literacy flows through people’s rites and practices, and it’s dynamism and vitality rest firmly on thoughts, emotions, movements, materials, spaces and places” (p. 1). Grounded on Street’s “utopian conception of literacy as always to come” (Pahl et al., 2020, p. 164) this foundational belief that literacy practices are embodied, bound within contexts, and ideological not solely autonomous, is woven throughout this research design. Literacy is both noun and verb, both lived and imagined in the endeavours of TEds striving to find the ephemeral, half-glimpsed spaces of the ‘not-yet’ (Pahl et al., 2020). As reflective of a P-IP research design, it is this living literacy practice within the OEPr of TEds that will be revealed through their lived experiences and intentionalities, as further described in the proposed research methodology.

For this research, the primary conceptualization for literacy/literacies recognizes that literacies are both an internal, cognitive ability and a social practice, with each requiring action and reflection. While Stordy’s (2015) taxonomies of literacies is particularly helpful as a starting point, there is potential for generating a phylogenetic representation to establish origin stories of literacy terminology, integrating information about inherited characteristics, and encompassing the full range of researchers in the field.