Finding educommunication: In search of praxis in Canadian educologies

Date Published: September 10, 2022.

This is a preprint, draft version of an upcoming publication. Here I share the unedited and unrevised version to capture elements that may become lost rather than found. This models my writing-in-action as a scholar.

Finding educommunication: In search of praxis in Canadian educologies

Abstract: Confronting increasingly challenging issues of inequality, disinformation, data surveillance, digital transformation, and globalization requires an informed and engaged citizenry. United Nations documents provide guidance to address the need for media empowerment in the ecology of everyday citizenship. Research suggests the necessity for open public spaces as locations for dialogue and communication. Educommunication, found predominantly within Latin American media education ecologies, may offer a path forward toward global engagement for proponents of critical media education. In the chapter, the concept of educommunication is examined and contrasted to conceptions of critical media literacy. Then results from a preliminary scan across Canadian educational spaces, with a specific focus on connections to teacher education programs, are shared. This chapter concludes with an invitation to continue national and international dialogues about educommunication and critical media education to support the development of informed, attentive, and educated media citizenship within a civic society.

Keywords: educommunication, critical media literacy, media education, Canada, teacher education

Introduction

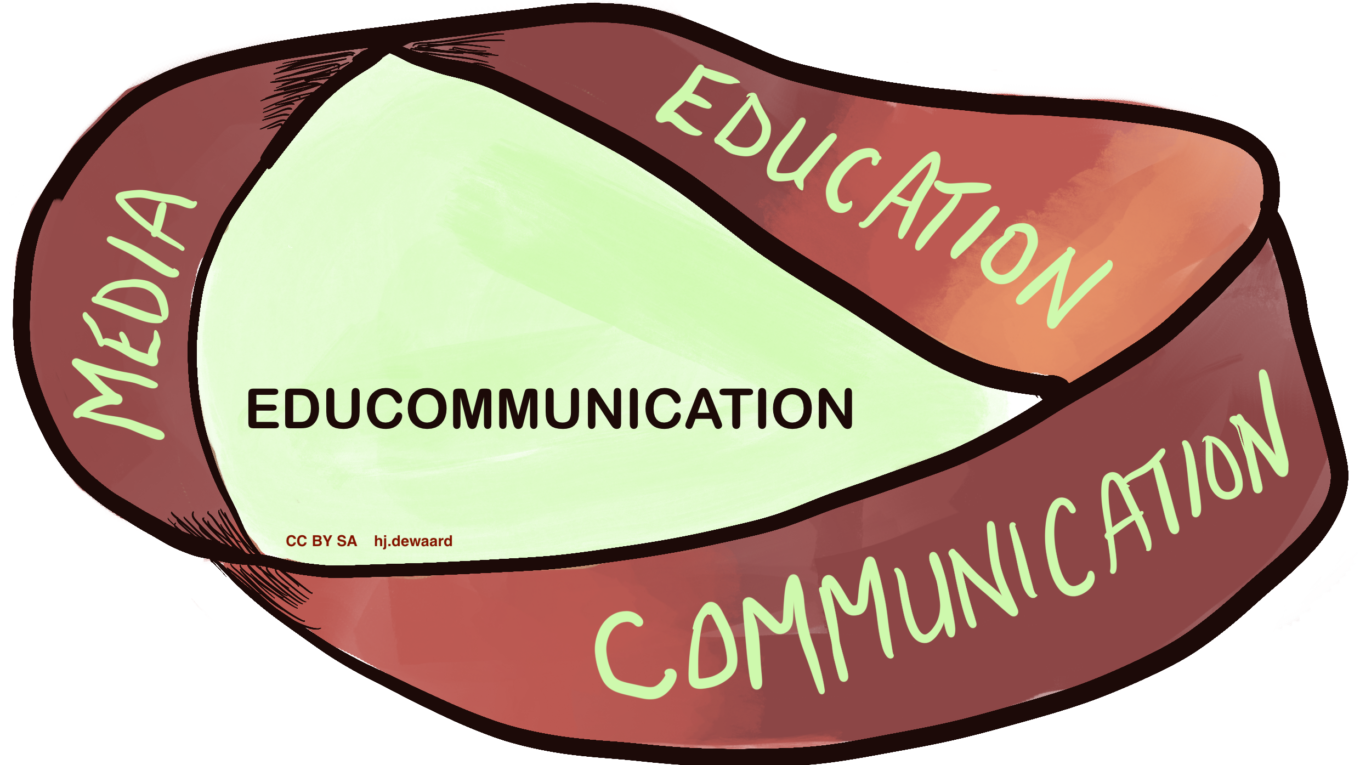

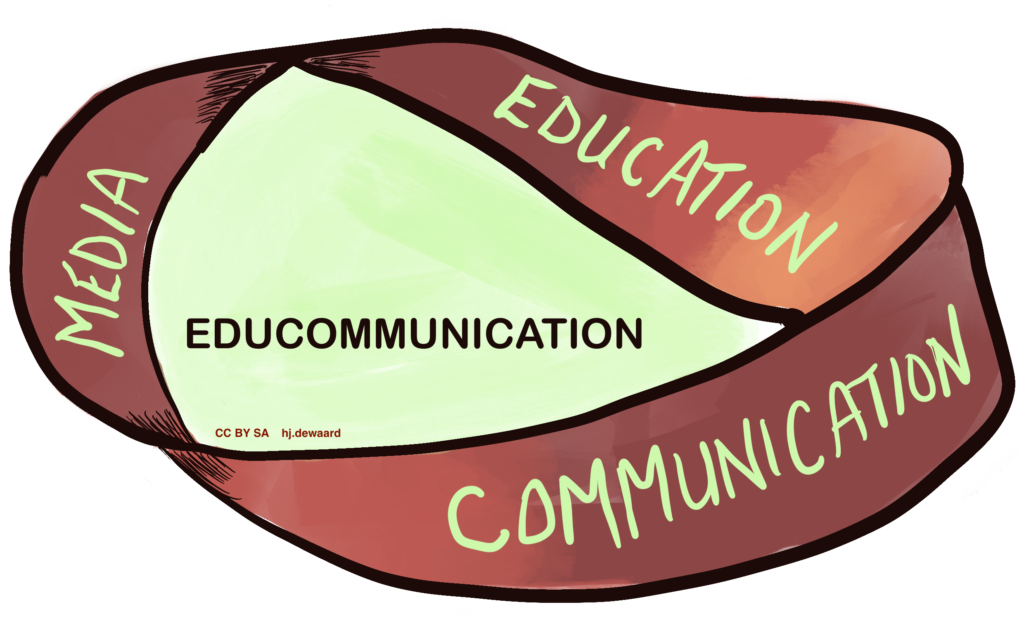

Media, education, and communication are intertwined within a mobius-style loop of complexity that involve popular culture, media consumption and creation, digital platform productions, navigations in networked collectives, and cultivating cultures. On one side of the loop is located the conception of educommunicación, and on the flip side is the conception of critical media literacy. One emerges from theory and research in Latin American contexts where education and communication are spliced together and the other dominates the field of media education in Anglocentric and Eurocentric contexts. In this chapter, these historically and conceptually disparate constructs are examined to provide an opportunity to untangle interwoven ideas. By doing so, some clarity may be gained.

While educommunicación theories and practices are widely known and impact educational contexts across Latin American countries, it is little known in the global north (Lombana-Bermudez, 2020; Mateus & Lombana-Bermudez, 2021; Torrent & Aparici, 2010). Educommunicación is a “sub domain of theory and practice that intersects between Media Studies, Journalism and Communications, on the one hand, and Education on the other” (Hoechsmann, 2019, p. 264). The concept of educommunicación falls under the broader idea of communication as activism involved in creating social change, with a socio-political praxis at its core (Barbas, 2020; Mateus & Quiroz, 2017). In Latin America, communication is “more about mediations than media, more about processes than objects” and the “processes and practices of people’s lived experiences with media form the backdrop to communication work” (Hoechsmann, 2019, p. 261). The education/communication intersection draws from community-based practices that engage citizen participation within an orientation toward transforming people’s lives (Barbas, 2020). In this chapter, the conception of educommunicación is referenced as educommunication.

In an effort to identify educommunicative practices within Canadian educational contexts, I focus on the praxis of educating for change, identifying locations and actions where synergies exist for faculties of education. As Share et al. (2019) contend, the integration of media into curriculum is not enough. This chapter is a response to a call to connect the “energies of instructors and researchers in Faculties of Education with activists in the non-profit youth-serving sector and the already existing network of teacher practitioners, media professionals, Ministry of Education curriculum developers, and non-profit organizations” (Hoechsmann & Poyntz, 2017, p. 10).

First the concepts and defining characteristics of educommunication and critical media literacy are examined. While a full exploration of the historical roots of educommunication or critical media literacy are beyond the scope of this chapter. Next, the results of a search for educommunication reveals praxis within Canadian educational ecologies (educologies). This chapter concludes with an urgent call to recognize educommunication as an “ecology of diverse knowledges and practices developed across different contexts” (Mateus & Lombana-Bermudez, 2021, paragraph 1) as discussions ofeducommunicational practices reverberate into global consciousness.

Defining educommunication

Educommunication, as defined by Oliveira Soares in 2003 and translated into English, is a:

set of actions inherent to planning, implementation and evaluation of processes, programs and products destined to create and strengthen communicative ecosystems in educational spaces, improve the communicative coefficient of educational actions, develop the critical spirit in users of mass media, adequately use information resources in educational practice and expand people’s expression capability (Freitas & Ferreira, 2020, p. 57).

Key elements of educommunication found in this and many of the definitions found in the research literature includes communication, education, activism, criticality, mass media and/or popular culture, and the enhancement of the expressive capacities of peoples (Barbas, 2020; Chiappe et al., 2020; Hoechsmann, 2019). Etymologically defined, it brings together the Latin derivative of ‘educere’ meaning to get from or extract, and the word ‘communicar’ with its underlying value of sharing and accessibility for all (Aguaded & Delgado-Ponce, 2019).

In the educommunication paradigm “an educational act is viewed as a communicational act, and a communicational act is an educational act” (Barbas, 2020, p. 74) and education is primarily a communicational endeavour (Chiappe et al., 2020). Such an educational approach is based on dialogue and views education as a liberating process enhanced by collective creation (Mateus & Lombana-Bermudez, 2021). Following a Freirean legacy, educommunicational processes are foundationally social, community driven, participatory, dialogic, and creating collectively construct knowledge (Aguaded & Delgado-Ponce, 2019; Barbas, 2020; Bermejo-Berros, 2021; Lago et al., 2021). Educommunication advocates a view of schools and schooling, including faculties of education, as undeniably embedded in local and global contexts, whereby education becomes responsibly involved in mediatization that “does not necessarily facilitate the communicative process, but rather creates new problems and challenges, and demands another type of more complex view” (Mateus & Lombana-Bermudez, 2021, para 14).

Educommunication is further framed by the Latin American notion of ‘lo popular’ that focuses, not on popular culture, but on the narratives and humour ‘of the people’ as mediations of media practices in everyday experiences (Rincon & Marroquin, 2020). This educational approach encompasses media practices that are grounded in current issues in communities. This suggests that educommunication ends the division between receivers and emitters of mass media (Aguaded & Delgado-Ponce, 2019; Torrent & Aparici, 2010). While media educational research may continue to separate the process of acquiring media skills and proficiencies through education in order to become media literate (Torrent & Aparici, 2010), educommunication provides a framework that encompasses purposeful and media related practices in the pursuit of communicating for civic purposes, which can lead to media citizenship (Gozálvez-Pérez & Contreras-Pulido, 2014).

Educommunication has “a civic purpose … endowed with an ethical, social, and democratic base that empowers citizens in their dealings with the media” (Gozálvez-Pérez & Contreras-Pulido, 2014, p. 130). Definitions emerging from The United Nations Educational, Scientific, Communications (UNESCO) frameworks for educommunication, media, and information literacy recognize multidisciplinary roles for intergovernmental organizations (Caldeiro Pedreira et al., 2019). Within community and school contexts, educommunicational practices often confront mass media and popular culture productions that negatively impact society in general and often impoverish or marginalize people and communities. Educommunicational practices include a collective call to action to make a difference for the good of the world, society, and individuals needing support (Barbas, 2020; Gozálvez-Pérez & Contreras-Pulido, 2014). Educommunication includes elements of social justice practices that may be found immersed in Global North critical media education, whereby media production is proposed to shape social change. In contrast, the focus for educommunication comes from the collective action of the people (Rincon & Marroquin, 2020).

Educommunication and Critical Media Education

Contexts and definitions need to be clarified and contrasted for greater understanding since there may emerge confusion between educommunication and critical media literacy (CML). While an exhaustive comparison is beyond the scope of this chapter, the next section is provided to bring understanding of essential differences.

Kellner and Share (2019) define CML as an interdisciplinary approach to teaching about media that empowers learners to utilize many forms of media tools and technologies to support education. This conception of CML emerges from the foundations of a) the social processes inherent in media construction and communication, b) analysis of the “languages, genres, codes, and conventions” (Kellner & Share, 2019, p. 19), c) how people negotiate meaning, d) examining underlying issues in representation, and e) critiquing institutional and corporate motivations and productions of media (Kellner & Share, 2019).

The first difference spotlights the CML focus on individual learners and the acquisition of literacy within a critical lens. This contrasts with the educommunicational application of community based, dialogic, and communicational actions within a collective group of individuals. For CML, this pursuit results in individual awareness of power dynamics while building knowledge for a purpose. The primary objective for educommunication is the pursuit of community-driven solidarity to address issues impacting their world. CML works from the inside-out, from the individual directives, actions, and knowledge mobilization engaging outward, toward to the world. Educommunicational processes work from the outside-in, initiated from community contexts, in community with others, driven by community initiatives, with work that engages people through education and communication, to use relevant and accessible media resources to solve problems.

The second contrast focuses on the underlying approach to CML as used by Kellner and Share (2007) and aligned to the notion of literacy as a “family of practices” (Robertson & Hughes, 2011, p. 40) with a protectionist view of media education. This applies both a media as art and media as social movement stances(Robertson & Hughes, 2011). Roberson and Hughes (2011) conclude in their research into the challenges of designing lessons to teach CML, and the emerging teaching practices of teacher candidates when learning about CML, that a stronger discourse, continuous exposure, and time to understand concepts will support the practice of teaching CML in teacher education and thus, in K-12 education. Robertson and Hughes (2011) echo Kellner and Share’s (2007) call for increased project-based media production and analyses, while taking action on social justice issues in teacher education. Educommunicational practices can provide a transformative approach to the inter-subjective and community driven mediational practices for communicational purposes (Mateus & Lombana-Bermudez, 2021). When infusing educommunicational practices into school and teaching contexts, the focus shifts to shared knowledge creation, collaborative production, and information mobilization. The underlying purpose for educommunicational approaches is on the transformation of the culture and community for the good ‘of the people’ while engaging in living experiences relating to community-based topics and issue.

Third, CML has transformative potential when integrated into FoE and K-12 classrooms, as it frequently leads to student activism and media productions to communicate about issues in local and global communities (Share et al., 2019). This brings a necessary connection between the educommunication and CML through shared focus on social activism within the study of education, media literacy, and communication. It is important for teacher education, and educators in the field, to look at the evolution and power of ideas found in popular media and popular culture (e.g. the use of the words “fake news”) to understand that “what we communicate, whom we communicate with, and how we are doing this communicating are inherently political” (Burkholder & Watt, 2017, p. 1).

Finally, educommunication and CML can become entangled with conceptions of social justice (SJ) or global citizen education (GCE). While there are commonalities that connect, the conceptual overlaps require some clarification for this chapter. In terms of SJ, Mihailidis et al., (2021) posit that CML is grounded on three core assumptions: media literacy creates knowledgeable individuals, empowers communities, and encourages democratic participation. Social justice is both process and goal to realize a fairer society which involves actions guided by principles of a) redistributive justice involving allocation of material and human resources to those in need, b) recognitive justice by recognizing and acknowledgment of human and societal differences, and c) representational justice involving equity in representation and political voice (Lambert, 2018). Likewise, global citizenship education, as described by the United Nations includes social, political, environmental, and economic actions of responsible individuals and communities on a global scale (UNESCO, n.d.). In conjunction with a focus on sustainable development goals, there is a call for universities around the world to responsibly promote global citizenship through education (Pluim, 2020), which can be integrated into an educommunicational approach to media literacy awareness. Educommunicational approaches enchance collaborative change initiatives with education focusing on community and world betterment, while CML education positions individual student learning activities as reflections of world and community events. In the next section, I examine the position of faculties of education as places ‘of the people’ where transformational educommunicational approaches could be realized.

Educommunication and Canadian Teacher Education

In Canada, due to the division of educational obligation into provincial and territorial responsibilities, described by Friesen and Jacobsen (2021) as a system of systems, there exists a multiplicity of processes, actions, teaching experiences, and faculty of education institutions working in isolation. Canadian educational contexts resemble an anthill, a metaphor used to describe a collective effort dependent on a “multiplicity of processes, actions and educommunication strategies that operate in isolation” (Mateus & Lombana-Bermudez, 2021b, para 9). While these efforts may advance an educommunicational educology, it should be done with awareness of others doing similar work. It is through an active use of open and shared communication strategies with web-based social networks that educators can unify actions and create networks (Mateus & Lombana-Bermudez, 2021a).

Canada is arguably recognized as a global leader of media education (Aguaded & Delgado-Ponce, 2019; DeWaard & Hoechsmann, 2021; Hoechsmann, 2019; Hoechsmann & Poyntz, 2017). The legacies of Canadian media influencers such as McLuhan, Duncan, Pungente, and Anderson (Hoechsmann & Poyntz, 2017; Rennie, 2015) ensure an active media awareness ecosphere within educational curricula across the country (Hoechsmann & DeWaard, 2015). While media literacy education is incorporated into provincial and territorial curriculum documents there are identified gaps (Gallagher & Rowsell, 2017). Likewise, there is little mention of media literacy within the program descriptions and course syllabi of Canadian faculties of education (Hennessey & Mueller, 2020). The critical role of teachers as “interpreters of national cultures, protectors of forms of particularity within civic communities, and mediators between tradition (past) and innovation (future)” (Kane et al., 2020, p. 11) cannot be overlooked.

Educommunication is considered an important factor in teacher education (Cortes et al., 2018; Gutiérrez-Martín et al., 2022; Hoechsmann & Poyntz, 2017). While Hoechsmann and Poyntz (2017) call for the introduction and augmentation for media literacy instruction in faculties of education, Cortes et al., (2018) posit an educommunicational perspective that calls on cultural issues to become embedded into communicational processes in teacher education in order to “address the political-technological perspective of the communicative ecosystem that limits and conditions the ways of being in the world”, thus “reallocating the discussion agenda to more complex aspects than merely the messages, the means” (Cortes et al., 2018, p. 13).

The anthill metaphor can also be applied to the multitude of national forums, provincial initiatives, non-profit organizational efforts, and local grassroots activism, where collaborative work occurs through multiple actions, projects, and processes that may or may not be connected to faculties of education in local locations. It is suggested that educommunication can “work with this proliferation of initiatives, but also encourage them and allow them to meet and work together” (J. C. Mateus & Lombana-Bermudez, 2021b). MediaSmarts Canada, a national non-profit organization supporting media and digital literacy initiatives, addresses this issue by calling for a national strategy with commitments to prioritize community-based and community-lead initiatives, as well as providing funding for community and school-based media and literacy training (McAleese & Brisson-Boivin, 2022).

Teacher education in Canada is a transitory space. Students, known as teacher candidates (TCs), attend for one to two years before moving into the workforce or into graduate studies. The challenge is to build authentic educommunicative opportunities for TCs to experience, learn collaboratively, and enact community-driven social change, all the while hoping that these activities and events will influence their emerging teaching practice (Cortes et al., 2018). Canadian student Ayush Chopra (Chopra, 2019) represents the voices of students across the country in calling for the integration of activism and academics. Educommunication approaches in faculties of education could enhance critical connections from learning about teaching to community-based activism.

Reading the Word and Reading the World

(Freire, 2018) positions education as a means for human persons of all ages and stages to read the word and read the world. In the following search I look beyond the integration of critical media education and examine engagement with word and world, whereby educational and communication promotes dialogue, and potentially impacts and transforms elements within local communities with/for marginalized peoples. Educommunication is revealed in engagements in civic and mediatic actions in the world and with the world, sharing media productions as a means for social action. This search into educommunicative actions in Canadian educational ecologies is a response to Hoechsmann and Poyntz’ (2017) call for stock-taking of media literacy initiatives. The resulting findings provide a cursory map of educologies where educators and grassroots organizations apply education and communication to read the word and the world in order to enhance the analysis and creation of media messages for the good of local, national, and global communities. I begin with a general exploration for educommunicational practices and not-for-profit organizations where education and communication facilitate dialogue and transform learning. I then search for educommunication potentials found in teaching about/with sustainable development goals (United Nations, 2015), climate education, and Indigenous educational activism resulting from truth and reconciliation initiatives.

With a motto that espouses learning with the world not just about it, the iEarn organization to connect people and projects in order to collaborate and transform understanding in over 140 countries (iEARN Collaboration Centre, n.d.). One project specific to teacher education is the Future Teachers Project where teacher educators are invited to participate in global conversations, thus enhancing communication, connection, and collaboration in the pursuit of education and transformation.

Since 1999, the Canadian non-profit organization TakingItGlobal has worked to create a “social network for social good” (TakingITGlobal, n.d.). This organization strategically engages and supports educators with opportunities to “empower young people to become agents of positive change in their local and global communities” (TakingITGlobal, n.d.). The Annual Report for 2021 identifies and celebrates progress in providing community service grants; supporting sustainable development goals; youth leadership funds; the Connected North project impacts and results; and the create to learn and learn to code initiatives (TakingITGlobal, 2021). Through this report, it is evident that community activism is evident in the actions and supports offered by this organization while connecting schools, teachers, and learners to local contextualized issues and concerns.

The Digital Human Library (DHL) was initiated by Canadian educator Leigh Cassell and connects school systems and classrooms across the country to people, topics, and activities from local to international contexts (Digital Human Library, n.d.b). This organization includes global connections for a wider reach to expand educommunicational opportunities. Registration is free to educators but is required to access the multitude of resources on the website. From the website and ongoing newsletter publications, this organization provides education about the foundational practices of experiential learning for teachers, video conferencing with experts, virtual tours and virtual reality with 360-degree panoramic views of sites within Canada and the world, live streaming of natural events and locations, and opportunities to volunteer with the DHL organization (Digital Human Library, n.d.a).

The Shoe Project is a grassroots educational initiative supporting immigrant and refugee women, and provides an opportunity to attend a writing workshop, followed by additional support and mentoring to complete a public performance of the memoir story created (The Shoe Project, 2021a). Catalyzing the stories through a pair of their shoes, this educommunicational work focuses media production and communication through education. While not specific to teacher education, this project can be woven into classes and courses in a faculty of education as a way to connect and enhance this educommunicational initiative. This example personally resonates for my work with teacher candidates since I frequently ask course participants to complete a ‘shoe selfie story’ as an introductory activity for online courses I teach. Putting the focus on a ‘third thing’ (Palmer, 2005) such as a pair of shoes can help break down barriers and free the imagination, allowing multimedia stories and critical media productions to emerge. The interactive map on the shoe project site can be explored for the shared stories about shoes (The Shoe Project, 2021b) that bring meaning to the journeys of not only the immigrant and refugee women who become immersed in Canadian contexts, but potentially for the teacher candidates who may become a classroom teacher in the home communities where immigrant and refugee women reside with their families.

VoicEd Radio is a curated collection of disparate voices from across Canada engaging with others from around the globe, to talk about education related topics (Welcome to VoicEd Radio, 2019). Originating with educator Stephen Hurley, this grassroots movement ‘of the people’ brings podcasts and recorded conversations into the forefront, just as the grassroots radio productions created in Latin American countries have modelled educommunication (Lombana-Bermudez, 2020). With ever-present internet bandwidth issues across the nation, this organization provides opportunities for others to listen, learn, and participate in the growing ecologies of Canadian education.

The Global Student Chat provides a platform and forum for students to build media and communication awareness with each other and for education related topics. Topics are varied but strategic support for digital citizenship, student safety online, and student voice are provided both on the site and through social media. The team of student leaders and chat ambassadors are facilitated by Canadian educators, providing a scheduled sequence of steps to engage in topics based on issues important to students (Global Student Chat, n.d.).

The Association of Media Literacy, an organization of teachers, librarians, parents, and media professionals, provides opportunities for “informed and critical understanding of the nature of media, their techniques, and their impact” (About the Association for Media Literacy (AML), 2022). Workshops and newsletters provide media focused information and resources important to teacher educators and teacher candidates across the country.

MediaSmarts Canada, a not-for-profit charitable organization provides strategic support through education, research, and communication to promote media and digital literacy in Canadian schools. Strategic examples include the annual Media Literacy week (Media Literacy Week, n.d.) along with the Digital Citizenship Day (Media Literacy Week: Digital Citizenship Day, n.d.); the blog site providing information and events relevant for parents, libraries, and educators; and the searchable database of curriculum connections for media education provided free to educators across Canada (About Us – MediaSmarts, n.d.).

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The United Nations sustainable development goals which identifies key areas for organizations and educators to focus (United Nations, 2015). Teacher-initiated organizations, communicating through the use of social media and web-based examples such as #Teach SDGs (n.d.) can educate others to teach about/with the sustainable development goals (SGDs). Extending this into applications of critical media education and educommunicative approaches, as students share projects to a wider audience, are evidenced in a presentation about SGDs in a Grade 2 project report (Our Journey into the Goals Project, 2012, p. 15). Projects can extend beyond learning about SDGs to include the application of critical media literacies to achieve learning. The Goals Project, a collection of SDG projects from around the globe (The Goals Project, n.d.), shares examples useful for teacher education and teacher candidates. Canadian educators and students are actively involved as part of the global team of collaborators, and facilitators [Bernadine Reeb (@berngill); Rola Tibshirani (@rolat)]. Including student voice is an important addition to educommunicative action, as modelled by Ayush Chopra (@Ayushchopra24)] who represents Canada as a youth ambassador. As an example, he advocates for collaborative action through the Goals Project (hashtag #GoalsProject), calling for environmental stewardship (Chopra, 2021).

Climate action

Climate activism has gained momentum globally. In Canada, and specifically in educational spaces, educommunicative connections are evident in the work by educators across Canada. Academic and organizational collaborations are multiple. Making research information public through website, social media, and communication platforms enhances these educommunication initiatives, not only in Canadian contexts, but through global partnerships. In teacher education today, it is essential to bring teacher candidates to understand and view the multitude of media texts surrounding climate action in education as representative of authorial interests and agendas, including those “texts that have a global reach and come in the form of advertising, branding, and sponsored content” (Damico et al., 2020, p. 688). Similarly, it is essential that teacher educators bring forward stories and living examples of climate action in school contexts, not merely as binary good or bad, but from an inquiry approach through which critical media examinations interrogate and challenge the views, values, and experiences of the teacher candidates themselves (Damico et al., 2020).

One such project is The Monitoring and Evaluating Climate Communication and Education (MECCE) project, strategically connected to the College of Education, University of Saskatchewan. This international research partnership focuses on educating and public awareness of climate change education and literacy development by supporting global monitoring, connecting regional hubs, sharing a digital library, communicating through a blog for public discourse, funding for case studies, and providing profiles of participating countries (The MECCE Project, 2022). As a result of this organization’s research and activism, changes to policies in Saskatchewan provides support for programming initiatives for K-12 students to gain “knowledge, and be active in sustainable living, engaged citizenship and well-being” (About SEPN, 2022). This organization models educommunication through their focus on communication and education through active use of website, blog, and e-news publications where scholarly research and reports are shared. Connections to SDGs and global citizenship education are evident.

Additionally, climate change education and research suggests that the “gap between Canadians’ high level of concern about climate change and their level of knowledge signifies a critical learning moment for both public and formal education” (Field et al., 2020). Teacher education faculties can capitalize on this need by partnering with organizations and activists to provide communicative media productions to educate about climate change policies and practices.

Indigenous Perspectives and Activism

With the important and emergent work from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015), the following collection of educational and communicational media productions is a partial scan of the some of the organizational and individual grassroots efforts of peoples across this nation to address systemic issues relevant to Indigenous Peoples. Many are turning to digital spaces to “share teachings, ways of knowing, and thinking about language, literacy, power and place”, thus revealing “distinct acts of civic engagement” (Burkholder & Watt, 2017, p. 2). These sites of activism offer a model of educommunicative approaches.

The Arramat project, connected to the University of Alberta, provides support for researchers and activists in the health and well-being of the environment around the globe, in an effort to strengthen Indigenous voices (Media release, 2022).

Sponsored by the First Nations University of Canada, the National Center for Collaboration in Indigenous Education (NCCIE) curates resources and suggested practices for Indigenous Education. This organization connects communities through educating and sharing stories about Indigenous education across Canada and around the world (Indigenous Education: The National Centre for Collaboration – About Us, 2020).

The Reconciliation through Indigenous Education course is a massive open online course offered in the Faculty of Education at the University of British Columbia (UBC PDCE, n.d.). This is offered annually to anyone interested in learning more about Indigenous history, world views, and approaches to learning. An introductory video with Dr. Jan Hare shows the value of a communicating a welcoming invitation to learn together and build understanding of a learning purpose.

Through the UBC faculty of education, educommunicational practices in action in teacher education focuses on Indigenous participants, learners, and teachers within the Northern Indigenous Teacher Education Program (NITEP) mentoring circle (Mentoring Circle, n.d.). From the NITEP website is a resource on decolonize teaching indigenizing learning, with the gathering and sharing of curriculum bundles designed by Indigenous educators for teachers across Canada (Welcome to Decolonizing Teaching Indigenizing Learning., n.d.). The site offers curriculum, curated resources, and social media links. Also through the NITEP website is evidence of how Indigenous community members are communicating and educating through popular media, providing opportunities to learn from the voices of Indigenous Peoples. (10 Indigenous TikTokers to Follow!, 2022)

The Water Walker (Mother Earth Water Walkers – Home, n.d.) and Junior Water Walker movements (Connect. Reflect. Respect. Protect., n.d.) combine education and communication for the purpose of increasing awareness of water related issues, particularly for Indigenous peoples. Multiple digital platforms (Google earth, Instagram, YouTube, and Twitter) support the many media productions by grassroots organizers to provide information, particularly for the annual water-walking event. This educommunicational opportunity can provide opportunities for purposeful media production for faculties of education, teacher educators, teacher candidates, and classroom teachers, as well as students and local communities. The NCCIE provides an opportunity to learn more about the Junior Water Walkers as an example of a ‘learn by doing’ educational practice (The Junior Water Walkers, n.d.).

CONCLUSION

As identified in the Grunwald Declaration (UNESCO, 1982) and reconfirmed in the Paris Agenda (Paris Declaration Calls for Renewed Emphasis on Media and Information Literacy in the Digital Age, 2014) media education mobilization is an urgent matter, requiring commitment at local, regional, provincial, national, and international levels of educational endeavour. No longer can actors and actions within the Canadian education sector anthill continue working without gaining a deeper knowledge and understanding of what is going on around them. This chapter precipitates and extends the dialogue for critical media literacy educators, educommunication researchers and practitioners (J. C. Mateus & Lombana-Bermudez, 2021a) and scholars in the field of media literacy to examine the nuanced differences and similarities between critical media literacy and educommunication (Hoechsmann, 2019). This search for meaningful ways to engage students and communities in the transformational work of media education may find that educommunication is a pathway forward.

This chapter offers the results of a search through various internet sites, media sources, and research literature for evidence of educommunicational practicesin action, all in an effort to bring greater understanding of where the Latin American concept of educommunication reverberates into the Canadian media educator’s consciousness. Within the Canadian educational spaces educologies, there are elusive threads that can lead to extending this dialogue about educommunication.

While the examples of found here may not resemble those found within the rich traditions exemplified in Latin America, these examples of educommunicative educologies across the country provide a window into the grassroots, community driven creation of alternative and educative media productions that are directly and indirectly connected to Canadian faculties of education. Cortes et al., (2018) reaffirms value in educative media education for a “plural, inclusive and participative society, since it gives prominence to the communicative process as a primarily “cultural” problem, subordinating the issues of the media” (p. 35).

In conclusion, I propose stronger connections between the ‘why’ for educational communication and the ‘how’ of creating, understanding, and analyzing media productions. Both are critical for the transformation of media literacy education, not only within faculties of education but the organizations working with marginalized people within local communities. Through the purposeful production of media projects that focus on the principles and practices of educommunication, critical and civic engagement can extend outward toward a greater focus on issues in global locations as envisioned by Lombana-Bermudez (2020). Canadian Henry Giroux posits “to be literate is not to be free, it is to be present and active in the struggle for reclaiming one’s voice, history and future” (Kellner & Share, 2019 p. 26). Educators, and specifically those in faculties of education, need to be actively involved in this struggle.

For many, critical media literacy education is suggested as a strategy for confronting global challenges and wicked problems in the renewal of civic life and positive media engagement (Carlsson, 2019). The conversation requires a shift in thinking and movement towards an “ecology of knowledges and practices of media literacy” … based on “dialogue, critical reflection, participation and collaboration, Educomunicación offers an alternative approach” (Lombana-Bermudez, 2020, conclusion section). Educommunication has potential to transform critical media literacy education into the vision expressed by bell hooks where “learning is a place where paradise can be created … we have the opportunity to labor for freedom … an openness of mind and heart that allows us to face reality even as we collectively imagine ways to move beyond boundaries” (hooks, 1994, p. 207).

References

10 Indigenous TikTokers to Follow! (2022, March 21). [University of British Columbia, Faculty of Education]. NITEP. https://nitep.educ.ubc.ca/march-21-2022-follow-indigenous-tiktok/

About SEPN. (2022). SEPN The Sustainability and Education Policy Network. https://sepn.ca/the-project/

About the Association for Media Literacy (AML). (2022). Association for Media Literacy. https://aml.ca/

About us—MediaSmarts. (n.d.). MediaSmarts Canada. https://mediasmarts.ca/about-us

Aguaded, I., & Delgado-Ponce, A. (2019). Educommunication. In R. Hobbs, P. Mihailidis, G. Cappello, M. Ranieri, & B. Thevenin (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of media literacy (pp. 1–6). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118978238.ieml0061

Barbas, A. (2020). Educommunication for social change. In H. Stephansen & E. Treré (Eds.), Citizen media and practice: Currents, connections, challenges (pp. 73–88). Routledge.

Beaudry, D. (2022, September 5). In Ojibwe our word for skywalkers is giizhigoong-bemsejig. Ojibwe art by James Mishibinijima @jamesmish41. https://twitter.com/DhkBeau/status/1566841650042884100

Bermejo-Berros, J. (2021). The critical dialogical method in Educommunication to develop narrative thinking. Comunicar, 29(67), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.3916/C67-2021-09

Bonnie Norton, FRSC. (n.d.). https://faculty.educ.ubc.ca/norton/

Brown, A., & Begoray, D. (2017). Using a graphic novel project to engage Indigenous youth in critical literacies. Language and Literacy, 19(3), 35. https://doi.org/10.20360/G2BT17

Burkholder, C., & Watt, D. (2017). Literacies of civic engagement: Negotiating digital, political and linguistic tensions. Language and Literacy, 19(3), 1–3.

Caldeiro Pedreira, M. C., Torres-Toukoumidis, A., Romero-Rodríguez, L. M., & Aguaded, I. (2019). The notion of educommunication in intergovernmental organizations. Vivat Academia, 0(148), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.148.23-40

Carlsson, U. (Ed.). (2019). Understanding media and information literacy (MIL) in the digital age. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/gmw2019_understanding_mil_ulla_carlsson.pdf

Chiappe, A., Amado, N., & Leguizamón, L. (2020). Educommunication in digital environments: An interaction´s perspective inside and beyond the classroom. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 6(1), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2020.v6i1.4959

Chopra, A. (2019, May). Wizard Ayusha goals project. https://twitter.com/Ayushchopra24

Chopra, A. (Director). (2021, February 15). Goals project week 4 | Environmental stewardship [YouTube]. https://youtu.be/_HoN3qactMc

Connect. Reflect. Respect. Protect. (n.d.). [Google]. The Junior Water Walkers. https://sites.google.com/tbcschools.ca/juniorwaterwalkers/history

Cortes, T. P. B. B., Martins, A. de O., & Souza, C. H. M. de. (2018). Media education, educommunication and teacher training: Parameters of the last 20 years of research on SciELO and Scopus databases. Educação em Revista, 34. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698200391

Damico, J. S., Baildon, M., & Panos, A. (2020). Climate justice literacy: Stories‐we‐live‐by, ecolinguistics, and classroom practice. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 63(6), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.1051

DeWaard, H., & Hoechsmann, M. (2021). Landscape and terrain of digital literacy policy and practice: Canada in the twenty‐first century. In D. Frau‐Meigs, S. Kotilainen, M. Pathak‐Shelat, M. Hoechsmann, & S. R. Poyntz (Eds.), Handbook on media education research: Contributions from an evolving field (pp. 363–371). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781119166900.ch34

Digital Human Library. (n.d.a). Frequently asked questions. https://www.digitalhumanlibrary.com/about/faq/

Digital Human Library. (n.d.b). Who we are. https://www.digitalhumanlibrary.com/about/

Field, D. E., Schwartzberg, P., Berger, D. P., & Gawron, S. (2020, February 26). Climate Change Education in the Canadian Classroom. EdCan Network. https://www.edcan.ca/articles/climate-change-education-canada/

Freire, P. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Bloomsburg (Original work published in 1970).

Freitas, J. V. de, & Ferreira, F. N. (2020). Socioenvironmental educommunication as a pedagogical strategy in early childhood education. Educação & Formação (Fortaleza), 54–72. https://doi.org/10.25053/redufor.v5i14mai/ago.1449in

Friesen, S., & Jacobsen, M. (2021). The education system of Canada: Foundations of the Canadian education system. In S. Jornitz & M. Parreira do Amaral (Eds.), The Education Systems of the Americas (pp. 291–311). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41651-5_37

Gallagher, T., & Rowsell, J. (2017). Untangling binaries: Where Canada sits in the “21st century debate.” McGill Journal of Education, 52(2), 383–407.

Global Student Chat. (n.d.). Welcome to #GlobalStudentChat. https://globaledsschat.com/

Gozálvez-Pérez, V., & Contreras-Pulido, P. (2014). Empowering media citizenship through educommunication. Comunicar: Revista Científica de Comunicación y Educación, 21(42), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.3916/C42-2014-12

Gutiérrez-Martín, A., Pinedo-González, R., & Gil-Puente, C. (2022). ICT and Media competencies of teachers. Convergence towards an integrated MIL-ICT model. Comunicar, 30(70), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.3916/C70-2022-02

Hennessey, E., & Mueller, J. (2020). Teaching and learning design thinking (DT): How do educators see DT fitting into the classroom? Canadian Journal of Education/Revue Canadienne de l’éducation, 43(2), 498–521.

Hoechsmann, M. (2019). Tan lejos pero tan cerca. The missing link between media literacy and educomunicación. In J.-C. Mateus, P. Andrada, & M.-T. Quiroz (Eds.), Media education in Latin America (1st ed., pp. 259–267). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429244469

Hoechsmann, M., & DeWaard, H. (2015). Mapping digital literacy policy and practice in the Canadian education landscape. Media Smarts Canada. http://mediasmarts.ca/sites/mediasmarts/files/publication-report/full/mapping-digital-literacy.pdf

Hoechsmann, M., & Poyntz, S. (2017). Learning and teaching media literacy in Canada: Embracing and transcending eclecticism. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.31390/taboo.12.1.04

hooks, bell. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

IEARN Collaboration Centre. (n.d.). IEARN: Learn with the World, Not Just about It. https://iearn.org/

Indigenous education: The national centre for collaboration—About us. (2020). NCCIE. https://www.nccie.ca/about-us/

Kane, R., Ng-A-Fook, N., Pinar, W., & Phelan, A., M. (2020). Reconceptualizing teacher education: A Canadian contribution to a global challenge. University of Ottawa Press.

Kellner, D., & Share, J. (2007). Critical media literacy, democracy, and the reconstruction of education. In D. Macedo & S. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Media literacy: A reader (pp. 3–23). Peter Lang.

Kellner, D., & Share, J. (2019). The critical media literacy guide: Engaging media and transforming education. Brill Sense.

Lago, C., Viana, C., Palma Mungioli, M. C., & Consani, M. (2021). Media education in Latin America: The paradigm of educommunication. In D. Frau-Meigs, S. Kotilainen, M. Pathak-Shelat, M. Hoechsmann, & S. Poyntz (Eds.), The handbook of media education research (1st ed., pp. 241–251). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Lambert, S. R. (2018). Changing our (dis)course: A distinctive social justice aligned definition of open education. Journal of Learning for Development, 5(3). https://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/290

Lombana-Bermudez, A. (2020, December 3). Re-discovering educommunicacion: The Latin American movement of media literacy education. Flow Journal.Org. https://www.flowjournal.org/2020/12/rediscovering-educomunicacions/

Mateus, J. C., & Lombana-Bermudez, A. (2021a, August 30). Educomunicación: Dialogues on Latin American media education (Part One) [Blog]. Henry Jenkins: Confessions of an Aca-Fan. http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2021/8/28/nbspeducomunicacinnbsp-dialogues-on-latin-american-media-education-part-one-in-a-series

Mateus, J. C., & Lombana-Bermudez, A. (2021b, September 1). Educomunicación matters: Media education in a pandemic and post pandemic world (Part 2) [Blog]. Henry Jenkins: Confessions of an Aca-Fan. http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2021/8/28/crsah6rpznev22804fd3aawry76w7w

Mateus, J. C., & Quiroz, M. T. (2017). Educommunication: A theoretical approach of studying media in school environments. Dialogos, 14(26), 152–163.

McAleese, S., & Brisson-Boivin, K. (2022). From access to engagement: A digital media literacy strategy for Canada. MediaSmarts. https://mediasmarts.ca/research-policy

Media literacy week. (n.d.). MLW – Teachers-Hub. https://mediasmarts.ca/mlw-teachers-hub

Media literacy week: Digital citizenship day. (n.d.). Media Literacy Week. https://mediasmarts.ca/digital-citizen-day

Media release. (2022, January 12). Arramat Project. https://arramatproject.org/media/

Mentoring Circle. (n.d.). [University of British Columbia]. Faculty of Education, NITEP. https://nitep.educ.ubc.ca/students/mentoring-circle/

Mihailidis, P., Ramasubramanian, S., Tully, M., Foster, B., Riewestahl, E., Johnson, P., & Angove, S. (2021). Do media literacies approach equity and justice? Journal of Media Literacy Education, 13(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2021-13-2-1

Mother earth water walkers—Home. (n.d.). [Wordpress]. Mother Earth Water Walker. http://www.motherearthwaterwalk.com/

Our journey into the goals project. (2012, September). GP_12_Journey. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/0045ea_76f9d60d16d64b198c4fa0117c718b6d.pdf

Palmer, P. J. (2005). A hidden wholeness: The journey toward an undivided life—An excerpt. In A hidden wholeness. https://www.spiritualityandpractice.com/book-reviews/excerpts/view/14443

Paris Declaration calls for renewed emphasis on media and information literacy in the digital age. (2014, July 3). MILUNESCO. https://milunesco.unaoc.org/mil-resources/paris-declaration-calls-for-renewed-emphasis-on-media-and-information-literacy-in-the-digital-age/

Pluim, G. (2020). Global citizenship education in international and comparative perspective: : Testimonies from emerging educators in Jamaica and Canada. Citizenship Education Research Journal/Revue de Recherche Sur l’éducation à La Citoyenneté, 8(1), 13–19.

Rennie, J. (2015). Making a scene: Producing media literacy narratives in Canada [PhD dissertation]. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.

Rincon, O., & Marroquin, A. (2020). The Latin American lo popular as a theory of communication. In H. C. Stephansen & E. Treré (Eds.), Citizen media and practice: Currents, connections, challenges. Routledge.

Robertson, L., & Hughes, J. M. (2011). Investigating preservice teachers’ understandings of critical media literacy. Language and Literacy, 13(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.20360/G22S35

Share, J., Mamikonyan, T., & Lopez, E. (2019). Critical media literacy in teacher education, theory, and practice. In J. Share, T. Mamikonyan, & E. Lopez, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1404

TakingITGlobal. (2021). 2021 Annual report. TakingITGlocal. https://takingitglobal.uberflip.com/i/1470156-takingitglobal-2021-annual-report/0?

TakingITGlobal. (n.d.). About TakingITGlobal. https://www.tigweb.org/about/

#Teach SDGs. (n.d.). http://www.teachsdgs.org

The Goals Project. (n.d.). Classrooms working on 17 Goals. Together. The Goals Project. https://www.goalsproject.org/

The Junior Water Walkers. (n.d.). Indigenous Education: The National Centre for Collaboration. https://www.nccie.ca/story/the-junior-water-walkers/

The MECCE project. (2022). MECCE – Home. https://mecce.ca/

The Shoe Project. (2021a). About the shoe project. https://theshoeproject.online/about-us

The Shoe Project. (2021b). The shoe project stories. https://theshoeprojectstories.com/

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission. (2015). Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: Calls to action. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/indigenous-people/aboriginal-peoples-documents/calls_to_action_english2.pdf

Torrent, J., & Aparici, R. (2010, February 10). Educommunication: Citizen participation and creativity. Media and Information Literacy Clearinghouse. https://milunesco.unaoc.org/mil-articles/educommunication-citizen-participation-and-creativity/

UBC PDCE. (n.d.). Reconciliation Through Indigenous Education [University of British Columbia, Faculty of Education]. Professional Development and Community Engagement. https://pdce.educ.ubc.ca/reconciliation/

UNESCO. (1982). Grunwald declaration on media education. https://milobs.pt/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/The-Gr%C3%BCnwald-Declaration-on-Media-Education.pdf

UNESCO. (n.d.). Global citizenship education. United Nations Academic Impact. https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/page/global-citizenship-education

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication

Welcome to Decolonizing Teaching Indigenizing Learning. (n.d.). [University of British Columbia, Faculty of Education]. Decolonizing Teaching Indigenizing Learning. https://indigenizinglearning.educ.ubc.ca/

Welcome to voicEd Radio. (2019). VoicEd Radio: Your Voice Is RIGHT Here! http://voiced.ca/

Appendix A

Educommunication: Graphic and description of the graphic

Appendix B

List of resources and websites presented in this chapter

10 Indigenous TikTokers to Follow! The Indigenous community on TikTok is using the digital platform to educate people on Indigenous issues and perspectives. (2022, March 21). [University of British Columbia, Faculty of Education]. NITEP.

About ICEC. (2022). Indigenous Continuing Education Centre. https://iceclearning.fnuniv.ca/

About SEPN. (2022). SEPN The Sustainability and Education Policy Network. https://sepn.ca/the-project/

About the Association for Media Literacy (AML). (2022). Association for Media Literacy. https://aml.ca/

About us – MediaSmarts. (n.d.). MediaSmarts Canada. https://mediasmarts.ca/about-us

African storybook – vision. (n.d.). https://africanstorybook.org/

Beaudry, D. (2022, September 5). In Ojibwe our word for skywalkers is giizhigoong-bemsejig. Ojibwe art by James Mishibinijima @jamesmish41. https://twitter.com/DhkBeau/status/1566841650042884100

CHENINE – Home. (2020). CHENINE – Change, Engagement, and Innovation in Education: A Canadian Collaboratory. https://chenine.ca/home-2/

Chopra, A. (2019, May). Wizard Ayusha goals project. https://twitter.com/Ayushchopra24

Chopra, A. (2021, February 15). Goals project week 4 | Environmental stewardship [YouTube]. https://youtu.be/_HoN3qactMc

Community Based & Web Based Programs. (2020). First Nations University of Canada. https://www.fnuniv.ca/academic/community-based-and-web-based-programs/

Connect. Reflect. Respect. Protect. (n.d.). [Google]. The Junior Water Walkers. https://sites.google.com/tbcschools.ca/juniorwaterwalkers/history

Digital Human Library. (n.d.a). Frequently asked questions. https://www.digitalhumanlibrary.com/about/faq/

Digital Human Library. (n.d.b). Who we are. https://www.digitalhumanlibrary.com/about/

Global Storybooks Portal. (n.d.). https://globalstorybooks.net/

Global Student Chat. (n.d.). Welcome to #GlobalStudentChat. https://globaledsschat.com/

Indigenous Education (NCCIE) Website Tools and Resources. (2022). NCCIE. https://iceclearning.fnuniv.ca/courses/nccie-website-tools-resources

Indigenous education: The national centre for collaboration – About us. (2020). NCCIE. https://www.nccie.ca/about-us/

Indigenous storybooks portal. (n.d.). https://indigenousstorybooks.ca/

Media literacy week. (n.d.). MLW – Teachers-Hub. https://mediasmarts.ca/mlw-teachers-hub

Media literacy week: Digital citizenship day. (n.d.). Media Literacy Week. https://mediasmarts.ca/digital-citizen-day

Media release. (2022, January 12). Arramat Project. https://arramatproject.org/media/

Mentoring Circle. (n.d.). [University of British Columbia]. Faculty of Education, NITEP. https://nitep.educ.ubc.ca/students/mentoring-circle/

Mother earth water walkers – Home. (n.d.). [Wordpress]. Mother Earth Water Walker. http://www.motherearthwaterwalk.com/

Our voices. (n.d.). Arramat Project. https://arramatproject.org/about/our-voices/

Paris Declaration calls for renewed emphasis on media and information literacy in the digital age. (2014, July 3). MILUNESCO. https://milunesco.unaoc.org/mil-resources/paris-declaration-calls-for-renewed-emphasis-on-media-and-information-literacy-in-the-digital-age/

Storybooks Canada. (n.d.). https://storybookscanada.ca/

TakingITGlobal. (2021). 2021 Annual report. TakingITGlocal. https://takingitglobal.uberflip.com/i/1470156-takingitglobal-2021-annual-report/0?

TakingITGlobal. (n.d.). About TakingITGlobal. https://www.tigweb.org/about/

The Arramat Project. (2022, January 6). A quote from Ărramăt Co-PI @danikabillie. https://twitter.com/ArramatProject/status/1486466614555922437?s=20&t=X5E3s1TL2J4hjFv5RfPQVw

The Canadian Playful Schools Network (CPSN) is the first of its kind in the world. (n.d.). Canadian Playful Schools Network. https://playjouer.ca/

The Goals Project. (n.d.). Classrooms working on 17 Goals. Together. The Goals Project. https://www.goalsproject.org/

The Junior Water Walkers. (n.d.). Indigenous Education: The National Centre for Collaboration. https://www.nccie.ca/story/the-junior-water-walkers/

The MECCE project. (2022). MECCE – Home. https://mecce.ca/

The Shoe Project. (2021a). About the shoe project. https://theshoeproject.online/about-us

The Shoe Project. (2021b). The shoe project stories. https://theshoeprojectstories.com/

UBC PDCE. (n.d.). Reconciliation Through Indigenous Education [University of British Columbia, Faculty of Education]. Professional Development and Community Engagement. https://pdce.educ.ubc.ca/reconciliation/

UNESCO. (1982). Grunwald declaration on media education. https://milobs.pt/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/The-Gr%C3%BCnwald-Declaration-on-Media-Education.pdf

Welcome to Decolonizing Teaching Indigenizing Learning. (n.d.). [University of British Columbia, Faculty of Education]. Decolonizing Teaching Indigenizing Learning. https://indigenizinglearning.educ.ubc.ca/

Welcome to voicEd Radio. (2019). VoicEd Radio: Your Voice Is RIGHT Here! http://voiced.ca/