Article Critique #1

This is the first of two article critiques for the Cognition and Learning course 6411.

The neuroscience of background knowledge: Building a schema about schema

Article Reference

Ghosh, V. & Gilboa, A. (2014). What is a memory schema? A historical perspective on current neuroscience literature. Neuropsychologia, 53, 104-114.

Statement about Article Selection

What I know and remember about background knowledge, more commonly referred to as prior knowledge or schema (Gilboa & Marlatte, 2017; Shing & Brod, 2016) is shaped by the structure and function of my schema of this concept. Since schema, a construct of memories resident in the brain, impacts learning and cognition (Lupo, Strong, Lewis, Walpole, & McKenna, 2017; Shing & Brod, 2016; Willingham, 2009), it is necessary to reframe my understanding about the role schema in the field of cognition and learning. Ghosh & Gilboa (2014), in What Is Memory Schema? A Historical Perspective on Current Neuroscience Literature, present a framework to conceptualize schema, share historical research of the concept, examine factors that define schema gained from psychology and neuroscience research, and present neurobiological information relevant to the structure of schema. This conception and definition of memory schema, with its intriguing connection between cognition and neuroscience, clarifies and extends my understanding of the necessary, sufficient, and additional features that shape how background knowledge is structured (Ghosh & Gilboa, 2014).

Connection to Chapter 3 in Willingham (2009)

Einstein got it wrong! Willingham (2009) advocates for knowledge over imagination, thus intimating that Einstein’s statement about imagination is incorrect (p.46). Willingham (2009) reflects that it is essential to understand the underlying structures of background knowledge, how it is encoded and retrieved, and how it is ‘instantiated’ (Gilboa & Marlatte, 2017), while advocating for knowledge acquisition, by suggesting that those with prior knowledge are advantaged to gain more knowledge (Lupo et al., 2017; Willingham, 2009). Through their review of psychological and neuroscientific research, Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) provide a framework or conceptualization of schema, by constructing associative networks, based on multiple episodes, which are adaptive and lack unit details. This echoes Willingham’s (2009) premise that as we acquire more factual knowledge with each new instantiation of information, the “rich get richer” (p. 45) and can more readily combine information in new ways (p. 28). While Willingham does not use the word schema, it is a common conception of background knowledge (Brod & Shing, 2016) thus is my attempt to build background knowledge – a schema about schema.

Article Summary

In order to develop a schema about schema, Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) examine the current and historical challenges in defining the concept of schema within the fields of psychology and neuroscientific research. Building understand of the defining characteristics of schema is done in order to “guide behavior, facilitate encoding, and enhance retrieval processes” (p. 113) which will aid knowledge building. The historical context examined by Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) references work of Head & Holmes (1911), Piaget (1926), and Bartlett (1932). This is followed by research into semantic networks as studied by Tulving (1974), the role of schema in reading comprehension examined by Anderson (1984), and computational modelling in relation to artificial intelligence by Schank (1983).

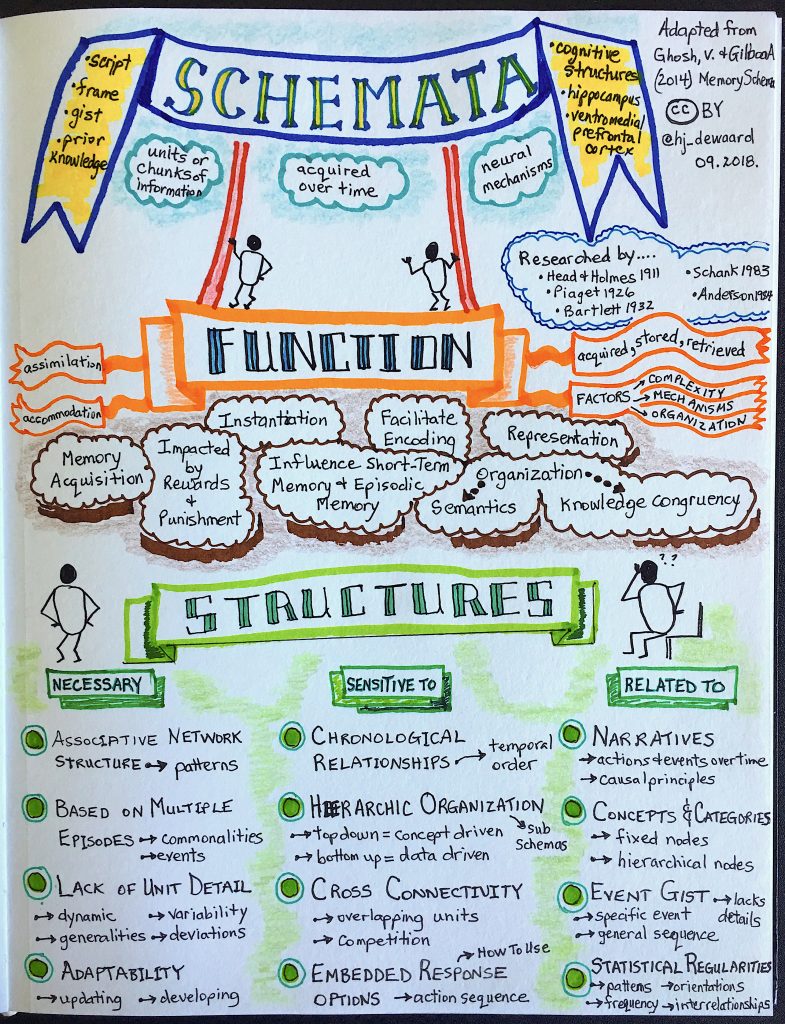

Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) propose a framework for memory schema (see Figure 1) by outlining four necessary features of schema:

- associative network structure defined as the interrelationships of units, more commonly referred to as ‘chunks’, based on patterns (p. 106),

- multiple episodes, considering commonalities between, and among, past and current acts (p. 106),

- lack of unit detail, perceived as a general overview, allowing for variability and flexibility of units, and tolerating deviations (p. 108), and

- adaptability, modelled on Piaget’s conceptions of assimilation and accommodation (p. 108).

Along with these necessary features, Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) outline four features that frequently impact schema structure:

- chronological relationships, such as ordering based on temporal sequences (p. 109),

- hierarchical organization, described as sub schemas based on top-down concept driven activation, or bottom-up data-driven activation, using a recursive progression (p. 109),

- cross-connectivity, describes communication between overlapping and associated units of information, sometimes competitive in nature (p. 109), and

- embedded response options, described as packets of knowledge which include directions for use of the information, sometimes referred to as an “action schema” (p. 109).

Further to these features, Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) define related cognitive structures that inform our understanding of schema:

- narratives, described as a “series of actions and events, that unfold over time, according to causal principles” (p. 110),

- concepts and categories, where nodes contain concepts within a network that describes categories where units of information are fixed and not adaptable (p. 110),

- event gists, seen as a general remembering of essential and coherent details of one occasion or event (p. 110), and

- statistical regularities, seen as being similar to schema but involves “non-declarative, procedural learning” (p. 110).

Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) conclude their exploration by applying this memory schema framework to eight neuroscientific studies, finding that all eight of the cognitive structures outlined in the framework were present in each of these studies. They conclude by examining the neurological influence of the prefrontal cortex section of the brain on schema development, hypothesizing that it is associated with the “activation of schema representations”, thus encouraging further study.

Critique

Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) begin by providing the reasoning for their analysis into a conceptualization of schema, based on a need for cross disciplinary understanding, between the fields of psychology, where the term schema has historical roots, and the field of cognitive neuroscience, where there is renewed interest, but little clarity, of the conception of schema. In their attempt to provide clarity and dispel ambiguity, it is unfortunate that their decisive conceptualization of schema, as shared in the final conclusion, is less than clear, from either a psychological or neuroscientific perspective (Shing & Brod, 2016; Gilboa & Marlatte, 2017). By limiting their definition to the structural composition of schema, and excluding the functional elements of schema development, their definition makes no reference to neural networks or mental models.

By providing a detailed and extensive historical perspective of the use and application of the term schema, Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) share the unique story of an idea from its earliest appearance in psychological research to current usage in educational psychology, thus providing some clarification and reframing of the evolution of the term. However, Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) neglect to recognize the philosophical influence of Immanuel Kant (Wood, Stoltz, Ness & Taylor, 2018) in this historical summary. Although Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) explore the neuroscience research later in their paper, there is no examination of historical perspectives of the term schema within neuroscience, even though this field of research is relatively new.

Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) explore the fuzzy edges of the concept of schema, as the blind men and the elephant do in an Indian poem, by examining the observable features (network, episodic, adaptable, unit detail), noting what influences schema (chronology, hierarchy, connectivity, action sequences), and outlining what is related but not part of schema (narratives, concepts and categories, event gist, statistical regularities). Unlike the blind men and the elephant, who can only rely on their own perspectives, Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) extensively review descriptions provided by others, through both psychology and neuroscientific research lenses, while at the same time limiting their conceptualization of schema by examining it from only a structural rather than functional formation of schemata (plural form of schema). This framework, as visualized in Figure 2, provides a clearer picture of the structural boundaries of schema.

Commendably, Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) provide this historical reframing of our understanding of schema, through this review of the literature, since advances in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and the neuroscience behind cognition, will continue to influence current conceptualizations of schema. From the neuroscientific perspective, Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) examine the role of two areas of the brain, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and the hippocampus (HPC), in the structure of schema. They determine that all eight of the neuroscientific research reports studied show that activation of the vmPFC fits into their proposed schema framework. They therefore determine that the vmPFC plays a significant role in the structural composition of schema. Ghosh & Gilboa (2014) suggest that both this role of the vmPFC in schema development, and their proposed framework for the structure of schema, be evaluated through future research endeavors.

Discussion Prompts

From a cognitive perspective, and based on your current understanding of how prior knowledge impacts student learning, describe your schema about schema? How would this re-structured description about schema alter or change your teaching practice to better support student learning?

References

Brod, G. & Shing, Y.L. (2018). Specifying the role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in memory formation. Neuropsychologia, 111, 8-15.

Ghosh, V. & Gilboa, A. (2014). What is a memory schema? A historical perspective on current neuroscience literature. Neuropsychologia, 53, 104-114.

Gilboa, A. & Marlatte, H. (2017). Neurobiology of schemas and schema-mediated memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(8), 618-631

Lupo, S., Strong, J., Lewis, W., Walpole, S., & McKenna, M. (2017). Building background knowledge through reading: Rethinking text sets. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 61(4), 433-444.

Shing, Y. L. & Brod, G. (2016). Effects of prior knowledge on memory: Implications for education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 10(3), 153-161.

Willingham, D. (2009). Why don’t students like school? San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Wood, M., Stoltz, D., Van Ness, J., & Taylor, M. (2018). Schemas and frames. Forthcoming in Sociological Theory, doi: 10.17605/OSF.10/B3U48. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Justin_Van_Ness/publication/323345621_Schemas_and_Frames/links/5aac06cdaca2721710f89f01/Schemas-and-Frames.pdf