Representation

Representation 4.0: Transforming educational research

This is a reading response for the Research Colloquium course for week 9. This response will focus on Korteweg’s (2014) conception of representations of research. While I agree with the call to “harness the opportunities that increasing digital fluency presents, and shape our research in ways that advance a more creative participatory culture in educational research” (Korteweg, 2014, p. 655), I suggest that Korteweg’s vision of representation 3.0 is far from being realized. Technology has surpassed what Korteweg (2014) and other researchers (AERA, 2019) envision as potential.

Knowledge translated into publicly engaging forms through immersive multimodal narratives and democratic participation is the goal of representations 3.0 – knowledge for the public and with the public.

Korteweg (2014), p. 662

With this statement Korteweg suggests that research and the representation of research endeavours will become public, democratically participatory, and multimodal. While this may be evident in some small ways in current educational research spaces, most is still closed off from public view, locked behind passwords, accessible through university paid portals, and is membership dependent. I will first examine the evolution of the web, as a place for multimodal representation. Then I will examine current research spaces for evidence of multimodal representation and ending with some suggestions for researchers to transform educational research.

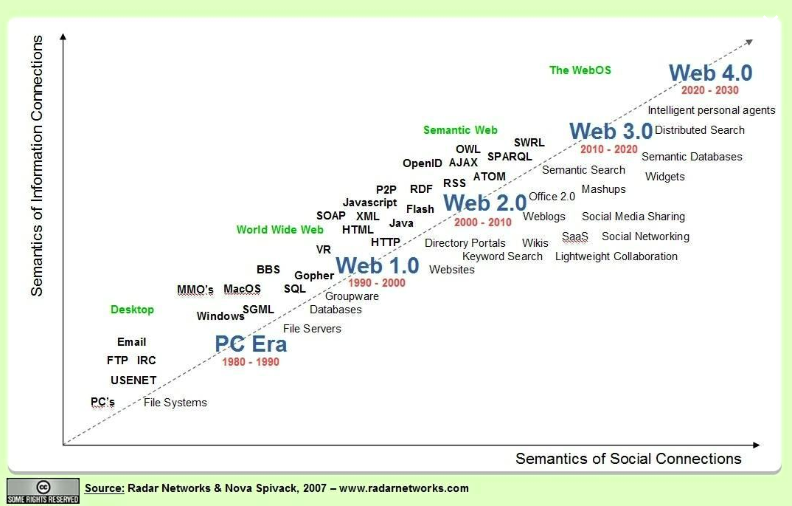

First, let’s look at this representation of the Web and imagine this as the space and place where all educational research comes to reside, in whatever form of presentation it is created.

- Web 1.0 – the web as repository of information, accessed by consumers in traditional uni-directional delivery systems (Korteweg, 2014; O’Reilly, 2005; Alexander, 2006)

- Web 2.0 – the web transitions to a ‘user-generated’ space where producer/consumer lines are blurred, cloud computing becomes a norm, social media engages many voices in multiple places. (Korteweg, 2014; O’Reilly, 2005; Alexander, 2006).

- Web 3.0 – user generated content is semantically interconnected using tags and folksonomies; the web becomes a place of knowledge construction, personal learning networks, and personal educational engagement and administration (Ohler, 2008).

- Web 4.0 – As we step towards 2020, the web as we know it is already evolving toward artificial intelligence as agentive knowledge builder, smart devices distributing information, and personal digital agents determining pragmatic actions (Almeida, 2017; Welgand & Paschke, 2012).

“Web 2.0 is the network as platform, spanning all connected devices; Web 2.0 applications are those that make the most of the intrinsic advantages of that platform: delivering software as a continually updated service that gets better the more people use it, consuming and remixing data from multiple sources, including individual users, while providing their own data and services in a form that allows remixing by others, creating network effects through an ‘architecture of participation’, and going beyond the page metaphor of Web 1.0 to deliver rich user experiences.”

O’Reilly (2005)

Understanding the variations in definitions between representations at the 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 levels is essential in order to conceptualize the future-focused potentialities of representations within today’s multi-medial digital environments at a 4.0 level. While Korteweg (2014) calls for re-invigorating the relevance and perspectives that are possible with Web 2.0 technologies, these are already dated in both conception and potential. With knowledge production and research representation that is connected, collaborative and networked, educational researchers can engaged in agentive actions together (Literat et al., 2018), as seen in this Ontario government initiative (KNAER, 2010).

How does this inform educational research and how it can be represented in current web-based spaces and places? With Web 4.0 approaching, will educational researchers be ready?

Within the field of educational research, representation is still privileged by text and bound by publication processes that are far from the transparent, open, free, authentic or presented in publicly engaged formats as championed by Korteweg (2014). While looking for alternative dissertation formats, as representative of multimodal production, to inform my own research representation, I notice that the most recent additions to the HASTAC Alt Diss space were posted in 2016. Using an incognito web search, to algorithmically remove prior search bias, the most recent results for ‘alternative dissertation’ are dated 2016. When searching, I differentiated between multimodal methods and multimodal representations to examine differences between research processes and the communication of research results. With this cursory glance, the sharing of multimodal research representations is attenuated, but worthy of further examination.

The AERA theme for the 2019 conference exhorts educational researchers to think about multimodality in research.

We must mobilize interdisciplinary and mixed-method bodies of evidence that coalesce to tell powerful, empirically driven, and multimodal narratives connecting the findings of advanced statistics to the lived experiences of educators, students, and parents across multiple contexts.

Stuart Wells, Jellison Holme, & Scott (n.d.)

Representations in today’s 4.0 digital environments, like its 2.0 predecessor, is emergent, uncertain, and contested (Alexander, 2008). Researchers working toward representations in 4.0 technologies will need to consider justifications and validations, just as they have done before. Representations not only have to address dialogue, scaling, recognition, and appeal (Korteweg, 2014) but also critical judgements (Scott, 2014), quality (Smith, 2014), and the politics of legitimizing their representations (Hodkinson, 2014) in order to extend Korteweg’s vision and renew AERA’s call for multimodal narratives.

But where can researchers start? Here are a few actionable items that can be taken by researchers.

- Re-present your ‘self’ as researcher and your research in multimodal manners. Sign up and register for an ORCID number to collect and connect to researchers and research beyond your current academic silos and echo chambers. Connect and converse with others using Twitter where informal and academic ‘chats’ occur, e.g. #unboundeq

- Look for non-traditional text-based formats including blogs, wikis, infographics, concept maps, and a variety of media (image, video, audio, typographics) and social media productions (YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Twitter, etc.). Weave these elements into research reports, discussion forums, and alternative dissertation locations. Push out of your comfort zones where text surrounds and binds you to the traditional. Extend into exploratory spaces where you can listen and learn e.g. VoiceEd Radio, Teaching in Higher Ed podcasts. Advocate for the use of specific modes of inquiry, analysis and representation the is the best fit for the research and argument (Literat et al., 2018).

- Find emerging publication options that promote multimodal production such as exemplified by The International Journal of Open Educational Resources and the OER Knowledge Cloud. See this article by Stephen Downes [A look at the future of open educational resources] as a model for multimodal publication. Scroll over underlined text to see what I mean by engaging and interactive.

- Start small, pick one, begin! If you want to start a research blog, build one. Connect it to one or two other researchers in your area of interest through an RSS feed. If you want to have conversations, join one. There are ongoing opportunities through Virtually Connecting. If you want to explore audio, try podcasting. Reach out to a podcaster and ask to be on their show e.g. Getting Air is one you can try. Become more web literate using current frameworks relating to researchers and academics, as modelled from my own experiences through eCampus Ontario [Extending My Thoughts]. Collect digital badges to display and share your acquisition of skills and proficiencies along the way.

- Learn more about copyright and Creative Commons licensing options. As a certified facilitator of the Creative Commons certification course, I will advocate for the need to know more about academic copyright, institutional policies relating to work product, and intellectual property rights that are enacted in the research work conducted as an employee and researcher.

Korteweg (2014) started this conversation. Literat et al., extend the challenge. It’s time to push into new ways for “challenging hegemonic conceptions regarding legitimate modes of scholarly inquiry, analysis and representation” (Literat et al., 2018, p. 566) in educational research. Awareness of representation in a Web 4.0 environment is only the beginning. Take one step at a time, but let’s take those first steps together.

References

Alexander, B. (2006). Web 2.0: A new wave of innovation for teaching and learning? Educause Review. Retrieved from https://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/erm0621.pdf

Literat, I., Conover, A., Herbert-Wasson, E., Kirsch Page, K., Riina-Ferrie, J., Stephens, R., Thanapornsangsuth, S., & Vasudevan, L., (2018). Toward multimodal inquiry: opportunities, challenges and implications of multimodality for research and scholarship, Higher Education Research & Development, 37(3), 565-578, DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2017.1389857

Ohler, J. (2008). The semantic web in education. Educause Quarterly. Retrieved Nov 3, 2019 from https://er.educause.edu/~/media/files/article-downloads/eqm0840.pdf

Ontario Government. (n.d.). Knowledge Network for Applied Education Research (KNAER). [website]. Retrieved Nov 3, 2019 from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/research/knowledge.html

O’Reilly, T. (2005, Sept. 30). What is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software. [website]. Retrieved Nov 3, 2019 from https://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

O’Reilly, T. (2005, Oct 1). Web 2.0: Compact definition? [weblog]. Retrieved from http://radar.oreilly.com/2005/10/web-20-compact-definition.html

Rogers, K. (2015). Rethinking the Dissertation: Opportunities Created by Emerging Technologies. Retrieved from https://mla.hcommons.org/deposits/objects/mla:374/datastreams/CONTENT/content

Stuart Wells, A., Jellison Holme, J., & Scott, J. T. (n.d.). 2019 Annual general meeting theme: Leveraging education research in a “post-truth” era: Multimodal narratives to democratize evidence. [website]. Retrieved Nov 3, 2019 from http://www.aera19.net/theme.html

What is ORCID? (n.d.) retrieved from https://support.orcid.org/hc/en-us/articles/360006973993-What-is-ORCID-