Quality in Educational Research

This is a reading response for the Research Colloquium course for week 9. This response focuses on the criteria and dimensions of determining quality in educational research as outlined in Scott (2014).

Scott outlines the internal, external, and parasitic criteria used to judge educational research. Scott presents an argument that questions how criteria for judging educational research are related and how the value of criteria are determined. While conceptions of criterial lists can be helpful in making judgements of a piece of research both systematic and transparent, Scott (2014) posits that assessors apply implicit and explicit criteria through an interpretive process that utilizes tacit judgements. Despite criterial lists, all “judgements about educational matters is inferential” and “the relationship between evidence and judgement is complicated” (p. 503).

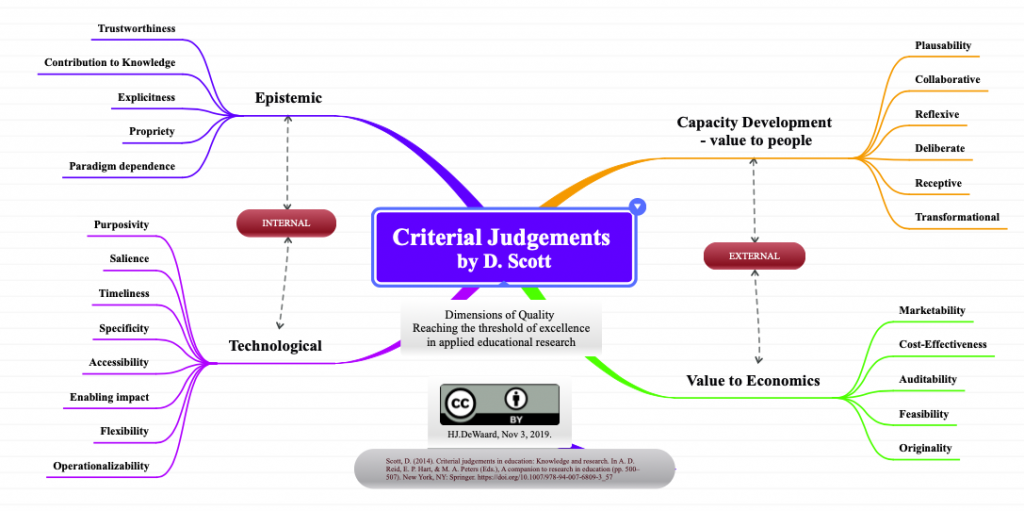

Scott suggests that it is one thing to apply criterial systems, such as the one proposed by Furlong and Oancea (see image below), but yet another to examine the fallibilism of both the researcher and assessor of the research piece. Scott (2014) posits that parasitic criteria, such as intentionality, transparency and plausibility, are reliant on the internal and external criteria for judging research and cannot be used without first judging these first order criteria. By examining these criterial lists, judgements can be made about epistemic, technological, and value of the research to make “on an agent or agency in the world” (Scott, 2014, p. 501).

While knowing how research is judged can be helpful to new researchers, these criterial lists should be used as guidelines, not rules to follow. Being able to succinctly reference criterial categories when writing a research report can improve the ability of a researcher to convince or justify the implicit and explicit elements upon which an assessor can judge the epistemic, technological, and value judgements.

Since claims and warrants are domain-specific, the judgement is dependent on the context and practice in which it is resides. While I acknowledge that others from outside my field of study may also judge my research, it is essential that I work toward internal and external criteria of value outlined in my domain. Scott (2014) outlines four reasons why evidence may not be specific to the claims being made, including “domain incommensurability”, non-conformity, insufficient probativity, and incompleteness (p. 503). In my case, the domain in which I will research is education with subdomains of literacy, educational technology, open education, and teacher education. Within these subdomains my research needs to demonstrate comparable epistemologies, topics, issues, research methodologies, and methods. My research should reflect frameworks evident in these domains, have probative value to the field or inquiry, and be complete in addressing the research criteria for this domain. Beyond this, I will also need to recognize the issues of fallibility when assessors judge my research, as outlined by Scott (2014), since “the degree and type of fallibility underpinning the epistemology used by the researcher or researchers in making their knowledge claims” (p. 503) will impact their judgements.

References

Scott, D. (2014). Criterial judgements in education: Knowledge and research. In A. D. Reid, E. P. Hart, & M. A. Peters (Eds.), A companion to research in education (pp. 500–507). New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6809-3_57

Image attribution and link: DeWaard, H. J. (2019, Nov. 3). Criterial judgements by D. Scott. Retrieved from https://www.mindomo.com/mindmap/1ad28f67973663f6a1d531614befa68b