3.0 Chapter 3. Research Design

In this section of the research proposal, I will explicate the methodology, methods, validity, and ethical considerations for this proposed research. While the methodological tools laid out for consideration in this research are reflective of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks I’ve examined in this proposal, I resist attempts to “impose a single, umbrella-like paradigm over the entire project” (Denzin, 2017, p. 10). At this early stage of this proposed research I attempt to “move forward into new spaces, into new identities, new relationships, and new radical forms of scholarship” (Denzin, 2017, p. 14). I will explicitly examine why post-intentional phenomenology and crystallization are responsive to research investigations with a focus on MDL and OEPr, and how these methodologies align with the theoretical frameworks shared thus far.

3.1. Methodology

“We seek those ruled by partial sight and limited voice-not partiality for its own sake but, rather, for the sake of the connections and unexpected openings situated knowledges make possible.” (Haraway, 1988, p. 590)

As Haraway suggests, it is through unexpected openings and partial sight that I will research the connections between MDL, OEPr and the TEds situated within FoE. In this next section of the research proposal, I will elaborate on the philosophical reasoning to why post-intentional phenomenology has been selected as the methodology and why crystallization will be the methodological approach that will be applied to this research.

3.1.1. Post-Intentional Phenomenology as Methodology

As a research methodology, post-intentional phenomenology (P-IP) brings together a focus on human-technology relations and a pragmatic approach to the study of ideas and experiences discovered within usage, design, policy, and research (Rosenberger & Verbeek, 2015). Further to this, P-IP studies extend the exploration of the “relations between human beings and technological artifacts” with a focus on ways technologies shape relationships between human beings and the world (Rosenberger & Verbeek, 2015, p. 9). P-IP studies have explored technological supports in an intercultural student community (Tannis, 2014), faculty’s lived experiences of adopting and using social networking sites (Veletsianos & Kimmons, 2013), and the lived experiences of being an adult learner in online environments (Pazurek-Tork, 2014).

Post-intentional phenomenologists begin with the technologies that shape human interactions, relationships, and embodiment (Ihde, 2011; Rosenberger & Verbeek, 2015). Following a P-IP approach, my research inquiry examines the lifeworld and lived experiences of TEds relationality (lived relation), corporeality (lived body), spatiality (lived space), temporality (lived time), and materiality (lived things and technologies), focusing on MDL within an OEPr (Rosenberger & Verbeek, 2015; Vagle, 2018).

While Rosenberger and Verbeek (2015) acknowledge the lack of a strict methodology for P-IP scholars to follow, they recognize central concepts and essential elements of those applying this methodology. P-IP research focuses on the “intentional relation between subject and object” since we always hear, see, feel, or think something (Rosenberger & Verbeek, 2015, p. 11). For post-intentional phenomenologists this intentionality explores the indirect and mediated relation between human-technology-world (Ihde, 2011; Rosenberger & Verbeek, 2015). This mediation is the “source of the specific shape that human subjectivity and the objectivity of the world can take in this specific situation. Subject and object are constituted in their mediated relation” (Rosenberger & Verbeek, 2015, p. 12) (emphasis in original source). Intentionality is the fountain from which subject and object emerge (Rosenberger & Verbeek, 2015).

For my research, this fountain is the intentionality of participants within the phenomenon of human-technology-world discovered through their MDL within OEPr, through which their human subjectivity is revealed. The objectivity of the digital world found within open educational networks, spaces, places, and events will be reflected within these intentional digital artifacts created and shared by the participants. The participants will reveal their awareness of MDL through this consciousness of the lived experiences of these micro-events and intentional actions taken, as shared in their stories.

Vagle (2018) suggests that P-IP researchers should follow lines of flight in three ways: first, by emphasizing connections “as a way to open up complicated movements and interactions” (p. 118); second by remaining “open, flexible, and contemplative in our thinking, acting, and decision-making” (p. 119); and, third by “resisting the tying down of lived experience and knowledge” (p. 119) to allow for unanticipated ways of knowing. With openness identified as a key consideration in P-IP research, there is an evident fit for an investigation into OEPr.

For this research, technology is an essential factor, particularly in light of current pandemic restrictions which heightens the role technology plays in mediating our world. Ihde (2011) posits that technology is not merely a tool through which we communicate. It is a “socially constructed cultural instrument in which current paradigms were an index of the sedimentation of beliefs” (Kennedy, 2016, p. 94). There exists a reflective arc between agent and world, as mediated through the technology (Ihde, 2011). It is through the active use of technology that TEds “find-ourselves-being-in-relation-with others … and other things” (Vagle, 2018, p. 20; emphasis in original). Thus, this P-IP research will examine the intentionality of technology within the phenomena being studied. A P-IP approach allows for a pathway that has “parameters, tools, techniques and guidance, but also allows us to be creative, exploratory, artistic and generative with our craft” (Vagle, 2014, p. 48). Reflexivity, a key feature of P-IP research, is described as a “dogged questioning of one’s own knowledge as opposed to a suspension of this knowledge” (Vagle, 2014, p 75) as posited in other phenomenological traditions as bracketing or bridling (van Manen, 2014).

Phenomenologists have an open stance to data gathering with a whole-part-whole analysis process. This process stems from the idea that phenomenologists think about “focal meanings (e.g. moments) in relation to the whole (e.g. broader context) from which they are situated” (Vagle, 2018, p. 108).

With this in mind, I will focus the research on the lived experiences and the nature of ‘becoming’ media and digitally literate that participant’s intentionality reveals in their open educational practices as teacher educators. It is through this “mediation and mutual constitution” (Rosenberger & Verbeek, 2015, p. 12) between subject and object, between teacher educator-artifact production-world of teacher education that I believe MDL and OEPr will emerge. P-IP methodologies apply a practical and material orientation in order to examine how human-technology-world relations are organized and emerge within human existence.

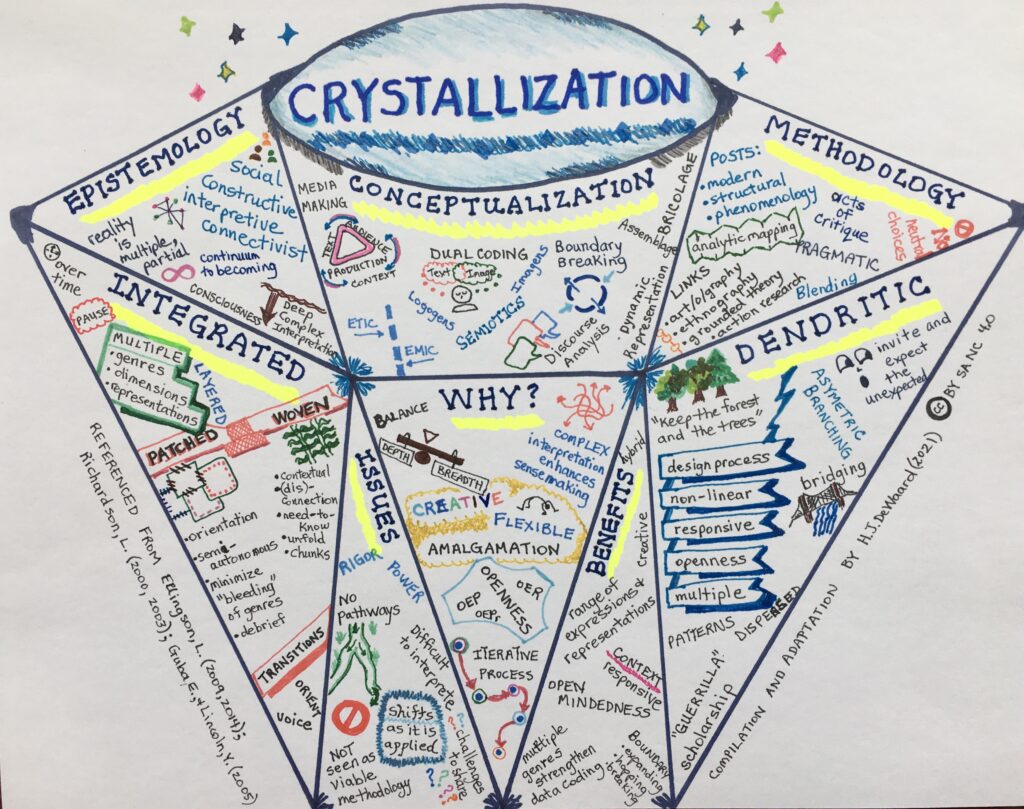

3.1.2. Crystallization Framework

Through my reading, and based on my experiences and interests in media making, I see crystallization as an approach that supports a P-IP research methodology. Despite the fact that crystallization may be seen as a challenging methodology requiring “sustained commitments to participants in the form of time, energy, and emotional labor” (Ellingson, 2014, p. 448), it is the creativity within the iterative readings and renderings that provides an exciting framework for my P-IP research methodology.

Crystallization can “build thick and rich descriptions through multiple forms, genres and modes to embed the researcher in a reflexive process allowing them to apply their craft” (Stewart et al., 2017, p. 3). In this way, as I craft research, my research reflexively crafts me.

Ellingson (2014) advocates for crystallization as a creative, flexible amalgamation of everyday stories rather than a specific set of strategies. I have selected a crystallization framework for multiple reasons. First, crystallization creates knowledge about a phenomenon by “generating a deepened, complex interpretation” (Ellingson, 2014, p. 444). Because teaching and teaching practices are relational, and the application of MDL to those practices, particularly within OEPr, are mediated through technologies, these relational moments can be seen, heard, felt, shared, analyzed and categorized in multiple, nuanced ways. Crystallization can reveal these multiple facets of the lived experiences of TEds in faculties of education.

Second, a crystallization framework “utilizes forms of analysis or ways of producing knowledge across multiple points of the qualitative continuum” (Ellingson, 2014, p. 444). By applying this framework to the P-IP methodology, I can open avenues to make sense of the data entanglements (Ellingson & Sotirin, 2020) found in the MDL and OEPr stories shared by TEds. My research will include variations of typology, visualizations, and pattern making to reveal rich descriptions of the data moments yet to be revealed.

Third, the multiple variations of texts and representations created within this research endeavor will depend on “segmenting, weaving, blending, or otherwise drawing upon two or more genres or ways of expressing findings” (Ellingson, 2014, p. 445). It is through the many media making productions of both the participants and myself as the researcher, that the stories of lived experiences with MDL and OEPr will be revealed.

Fourth, crystallization requires “a significant degree of reflexive consideration of the researcher’s self in the process of research design, data collection, and representation” (Ellingson, 2014, p. 446). Within the P-IP methodology this reflexivity will critically examine the non-neutrality of technologies as it simultaneously amplifies and reduces (Kennedy, 2016) the mediations within the OEPr of TEds. Researcher reflexivity within this research is furthered by McLuhan’s tetrad of media effects that influence technological/mediums in terms of what is enhanced, retrieved, obsolesced, and reversed (Kelly, 2011).

Fifth, crystallization fits P-IP methodologies as it “embraces, reveals, and even celebrates knowledge as inevitably situated, partial, constructed, multiple, and embodied” (Ellingson, 2014, p. 446). Like P-IP methodologies, crystallization has no pathway or formal structure but follows an emerging design that is both integrative and dendritic (Ellingson, 2009), while the data entanglements (Ellingson & Sotirin, 2020) are woven, patched, layered, blended, dispersed, and disparate.

To be true to the orientation of wonder that is an essential methodological aspect of P-IP inquiry, I will infuse crystallization strategies when engaging with data while exploring both etic and emic discourse analysis (Gee, 2011) to the MDL within OEPr of TEds. I will engage with data while iteratively applying coding strategies (Saldaña, 2016) to the lived-experience stories, images, and media shared by the participants, in order to be attentive to the “sudden realization of the unsuspected enigmatic nature of ordinary reality” (Van Manen, 2014, p. 360).