2.2.2 Open Education

2.2.2. Open Education

Open education (OE) includes the “simple and powerful idea that the world’s knowledge is a public good and that technology in general and the Web in particular provide an extraordinary opportunity for everyone to share, use, and reuse knowledge” (Geser, 2012). Openly available technologies, education and scholarship are a “shared enterprise, a communal act” (Blomgren, 2018, p. 64). From this vision, Wiley and Hilton’s (2018) conception for the integration and application of the five R’s of reuse, revision, remixing, retention, and redistributing resources within pedagogical practices shapes the conception of an open teaching practice. The following conceptualization of open education frames my work:

Open education is a way of carrying out education, often using digital technologies. Its aim is to widen access and participation to everyone by removing barriers and making learning accessible, abundant, and customisable for all. It offers multiple ways of teaching and learning, building and sharing knowledge. It also provides a variety of access routes to formal and non-formal education, and connects the two (Inamorato dos Santos, 2019, p. 6).

This definition is framed in the UNESCO document Opening Up Education where a ten-dimensional framework outlines six core dimensions (access, content, pedagogy, recognition, collaboration, and research) supported by four transversal dimensions (strategy, technology, quality, and leadership) (Inamorato dos Santos et al., 2016). This framework is helpful in understanding the construct of open education.

Stories abound in the field of open education – #101OpenStories. OE predates digital technologies (Noddings & Enright, 1983). OE is not constrained or limited to digital resource production, digitally enabled teaching and learning, or electronic distribution of learning materials. However, for this research, digital is a primary component of open education. Cronin and MacLaren (2018) posit the extensive reach of open education conceptions to describe “not just policy, practices, resources, curricula and pedagogy, but also the values inherent within these, as well as relationships between teachers and learners” (p. 217). That being said, there are many conceptions, definitions, and visions for open education in relation to:

- open educational resources (Bayne et al., 2015; Rolfe, 2012; Weller, 2014);

- open scholarship (Stewart, 2015; Veletsianos, 2015; Weller, 2016);

- open education movement (Alevizou, 2015; Couros, 2006; Farrow, 2016; Rolfe, 2017);

- open pedagogies (Armellini & Nie, 2013; Hegarty, 2015; Paskevicius & Irvine, 2019; Wiley & Hilton, 2018); and

- open education practices (Couros, 2010; Cronin & MacLaren, 2018; Paskevicius, 2017; Roberts et al., 2018; Roberts, 2019; Stagg, 2017).

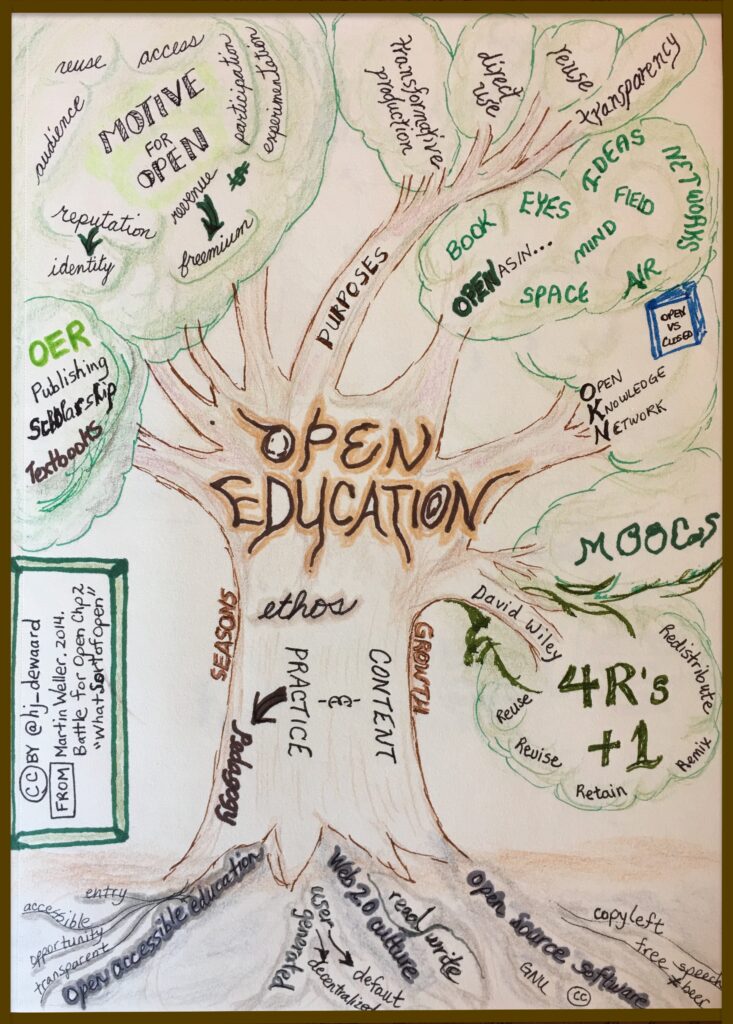

While the dominant research discourse focuses on open educational resources (OER) my research will focus on the transformative potential of OEPr, which is underrepresented in scholarly work, particularly in the field of education (Cronin & MacLaren, 2018; Nascimbeni, 2018; Paskevicius, 2018; Roberts, 2019; Tur et al., 2020). Figure 2 illuminates some of the key elements found in open education contexts.

For clarification, I differentiate between open education practices using OEPr, rather than the usually applied acronym OEP which is commonly applied to both open pedagogies and open practices. In this way I hope to add to the evolution of this term and provide clarity in naming this concept. I will next define OER, explore a framework for open pedagogy, and elaborate on conceptions of OEPr.

OER: Open Resources

Open educational resources (OER) are free, openly accessible, openly licensed educational materials (text, media, and digital assets) that can be used for teaching, learning, research, and other purposes (UNESCO, 2019a). The term OER encompasses publicly accessible materials available to anyone to reuse, remix, revise, improve and redistribute (Wiley & Hilton, 2018) under license formats that frequently include Creative Commons licensing frameworks. While the use and application of OER has transformative potential when the benefits of sharing across institutions and countries are fully realized, it relies on individuals in educational settings to become open in the ways “they produce and share knowledge, in the way they teach and assess students, and in collaborating with others” (Inamorato dos Santos, 2019, p. 7).

Since the Cape Town Open Education Declaration in 2007and 2012 Paris OER Declaration (UNESCO, 2012a), the United Nations and UNESCO have advocated and promoted the use and creation of OER (Hodgkinson-Williams & Gray, 2009) to uphold open education initiatives in support of the SDGs in education (UNESCO, 2012b). In 2017, the Ljubljana Action Plan provided direction in building capacity, ensuring inclusive and equitable access, and developing sustainability models for the development of policy and environments for OER (Jožef Stefan Institute Centre for Knowledge Transfer in Information Technologies, 2020). In 2019, the UN General Conference adopted a recommendation outlining five areas of action for OER: a) build capacity to create, access, re-use, adapt and redistribute OER; b) foster supporting policies; c) inspire inclusive, accessible, and equitable OER; d) develop models to sustain OER; and e) accelerate international teamwork (UNESCO, 2019a). This sets a global direction for OER to be recognized and supported as an area for growth within each country. Here in Canada, the development of OER and open education relies on provincially funded educational initiatives. A pan-Canadian organization is helping to open up the traditionally siloed educational K-20+ sector (“Canada’s Open Education Initiatives,” n.d.). Networks of educators are building collaborative OER as part of course work, with students as active agents of information generation. For this research, the primary focus will not be on the production of OER but rather the shift in teaching practices that may or may not include the use, creation, or assessment of OER.

OEP: Open Pedagogy

Open educational pedagogy (OEP) overlaps with open educational practices (OEPr) so building understanding requires some exploration. Finding the edges of the concept of OEP will help clarify the conception of OEPr that is essential to my research. While neither ‘open’ or ‘pedagogy’ is defined or delineated by the use of digital technologies, the conception I apply is bounded by the use of electronic and web-based tools and resources. Within this boundary, the use of OER is not a required condition for OEP. For the purpose of my research, open pedagogies are those that are digital but not always licensed for remix or reuse.

Open educational pedagogies, sometimes referred to as open teaching (Couros, 2010; Nascimbeni & Burgos, 2016), are defined as teaching and learning habits, facilitated and supported by open educators, involve making or using OER, engage students in creating OER, and the sharing of accessible professional materials (Cronin, 2017b; Farrow, 2015). The Cape Town Open Education Declaration suggests that, beyond using OER, open education includes “collaborative, flexible learning and the open sharing of teaching practices that empower educators to benefit from the best ideas of their colleagues … to include new approaches to assessment, accreditation and collaborative learning” (The Cape Town open education declaration, 2007, para 4). As shared by McAndrew and Farrow (2013), the International Council for Open and Distance Education declares OEP to include the creation, use and repurposing of quality OER that is supported by institutional policies. Veletsianos (2015) suggests a distinction between OEP licensing and OEP sharing cultures, relating to making artifacts or activities to engage with others.

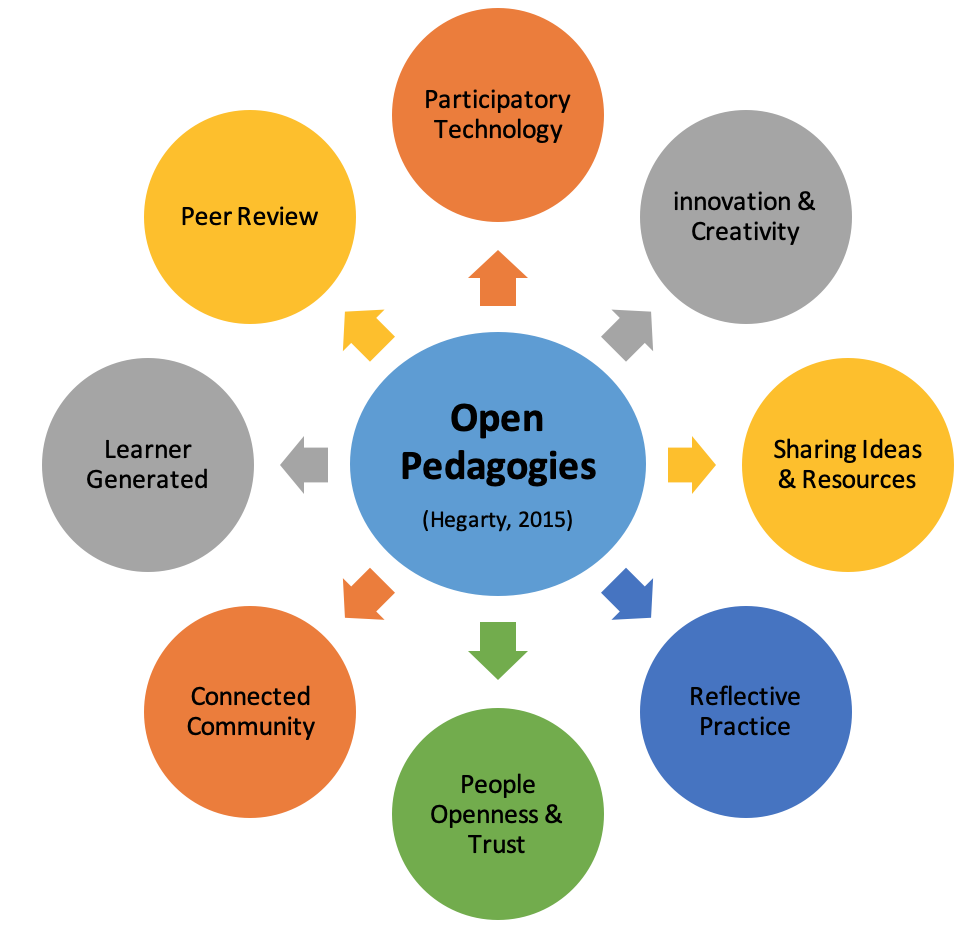

Hegarty (2015) explored open pedagogies by applying eight attributes – learner generated, connected community, peer review, participatory technology, innovation and creativity, sharing ideas and resources, people openness and trust, and reflective practice (see Figure 3). These attributes rely on digital tools and resources but also envelop the skills and attitudes of educators and learners (Hegarty, 2015). Open pedagogies bring a high degree of sharing and authentic, agentic action into learning spaces but relies on learner self-regulation and learning needs (Hegarty, 2015). Educators who enact open pedagogies provide openly accessible, openly managed, socially engaging, experiential, and scaffolded learning events and assets as co-facilitators and catalysts for learning (Ehlers, 2011; Hegarty, 2015).

Open pedagogy is further defined as a:

site of praxis, a place where theories about learning, teaching, technology, and social justice enter into a conversation with each other and inform the development of educational practices and structures. This site is dynamic, contested, constantly under revision, and resists static definitional claims. But it is not a site vacant of meaning or political conviction.

Jhangiani & DeRosa, 2018.

This definition suggests an evolving understanding of what open pedagogy means and points toward the praxis/practices in education that enable openness. In this way, pedagogy moves beyond the collection of educational ‘stuff’ and shifts toward an orientation, a “quality held by educators themselves”, and a description of an educational identity (Tur et al., 2020, p. 4). For this research, I consider open pedagogies (OEP) as a subset encompassed by the broader term of OEPr.

OEPr: Open Practices

Despite more than a decade of developing conceptualizations of OEPr, as shaped by social, cultural, geographic, and economic factors, there is still no clear definition of what it means to be an open educator (Bozkurt et al., 2019; Cronin & MacLaren, 2018). Broadly speaking, OEPr encompasses (a) open sharing of learning and instructional design, (b) collaborative development of open educational content and resources, (c) open and accessible co-creation and delivery of learning activities, and (d) the application of shared peer and collaborative assessment and evaluation practices (Bozkurt et al., 2019; Cronin & MacLaren, 2018; Nascimbeni & Burgos, 2016; Paskevicius, 2017; Wiley & Hilton, 2018). Openness in education results in increased transparency, improved collaboration, and the democratization of educational endeavours (Kimmons, 2016). This definition of OEPr is shaped by a philosophy about teaching that “emphasizes giving learners choices about medium or media, place of study, pace of study, support mechanisms, and entry and exit points, which are provided mostly with opportunities enabled by educational technologies” (Bozkurt et al., 2019, p. 80).

OEPr can be more narrowly defined by identifying skills and abilities educators apply when opening their teaching and learning environments by removing barriers to learning (Cronin, 2017; Nascimbeni & Burgos, 2016). Paskevicius (2017) defined OEPr as “practices where openness is enacted within all aspects of instructional practice; including the design of learning outcomes, the selection of teaching resources, and the planning of activities and assessment” (p. 127). For my research, I will explore the OEPr of teacher educators as they engage and participate, create and network, select learning objects, and/or apply Creative Commons licensing (Paskevicius, 2017; Watt, 2019).

Nascimbeni and Burgos (2016) attempted to identify and measure the qualities of an open educator using their Open Educators Factory (OEF) which examined elements of teaching practice such as openly designing learning, developing and using open content, teaching openly, and applying assessment that shifts beyond the notion of a disposable assignment (Nascimbeni & Burgos, 2016; Paskevicius, 2018; Wiley & Hilton, 2018).

An Open Educator chooses to use open approaches, when possible and appropriate, with the aim to remove all unnecessary barriers to learning. He/she works through an open online identity and relies on online social networking to enrich and implement his/her work, understanding that collaboration bears a responsibility towards the work of others.

Nascimbeni & Burgos, 2016, p. 4

Tur et al., (2020) examined this notion of becoming an open educator and enacting an OEPr as reflected in an open identity examined through the lens of threshold concepts, best described as “capabilities, skills, experiences or practices and of which might also indicate ways of thinking, practicing and being which act to signal membership of, or changing status within, a community of practice” (p. 5). Gee’s (2017) notion of “being” and “becoming” highlights this internal state, in this case being an open educator, and the transition an educator undergoes in becoming, through rights-of-passage involving doing (experiences), sense making (knowledge) and identities (being) that are transformative, troublesome, and liminal (Tur et al., 2020).

In an attempt to provide further distinction between OEPr as action and event driven, to one that is internal, Cronin’s (2017) clarification of openness as “individual, complex and contextual” (p. 18) is a helpful starting point. Cronin’s (2016) conception of openness, brings to the forefront the individual to whom the open practice matters as an educator, situated within the contextualized, complex spaces where personal identity, on multiple levels, is continually negotiated, and where personal and connected decisions are made, both within and from outside educational contexts (Cronin, 2016). This is where the conceptualization of OEPr is reframed as individual, online identity building, hospitable, negotiated and reflective.

A holistic conception of teaching practice as open is proposed here. Cronin’s (2016) notion of openness can be juxtaposed with the writing of Parker J. Palmer (2017), who described three entanglements in teaching. First is the content or subject matter that must be managed. Second is the complexity brought to the teaching environment as embodied in each student. Palmer (2017) suggested the greatest challenge comes from within each educator since “we teach who we are” (p. 2). Palmer (2017) stated:

Teaching, like any truly human activity, emerges from one’s inwardness, for better or worse. … The entanglements I experience in the classroom are often no more or less than the convolutions of my inner life. Viewed from this angle, teaching holds a mirror to the soul. If I am willing to look in that mirror, and not run from what I see, I have a chance to gain self-knowledge—and knowing myself is as crucial to good teaching as knowing my students and my subject.

Palmer, 2017, p. 3

When thinking about OEPr, it is into open education spaces that TEds project their inner selves, as they become both a mirror and a window (Style, 1988) and where their teaching is openly displayed in all the layers, negotiations, tasks, actions, and care encompassed within the art of teaching. In open educational contexts, OEPr is a reflection of everything TEds are and do as a teacher. The digital technologies and resources they select, use and integrate into the courses they teach will mirror their personality, persona and identity, both physical and digital. TEds reveal, either physically or virtually, their identity and selfhood since “good teaching cannot be reduced to technique; good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher” (Palmer, 2017, p. 4).

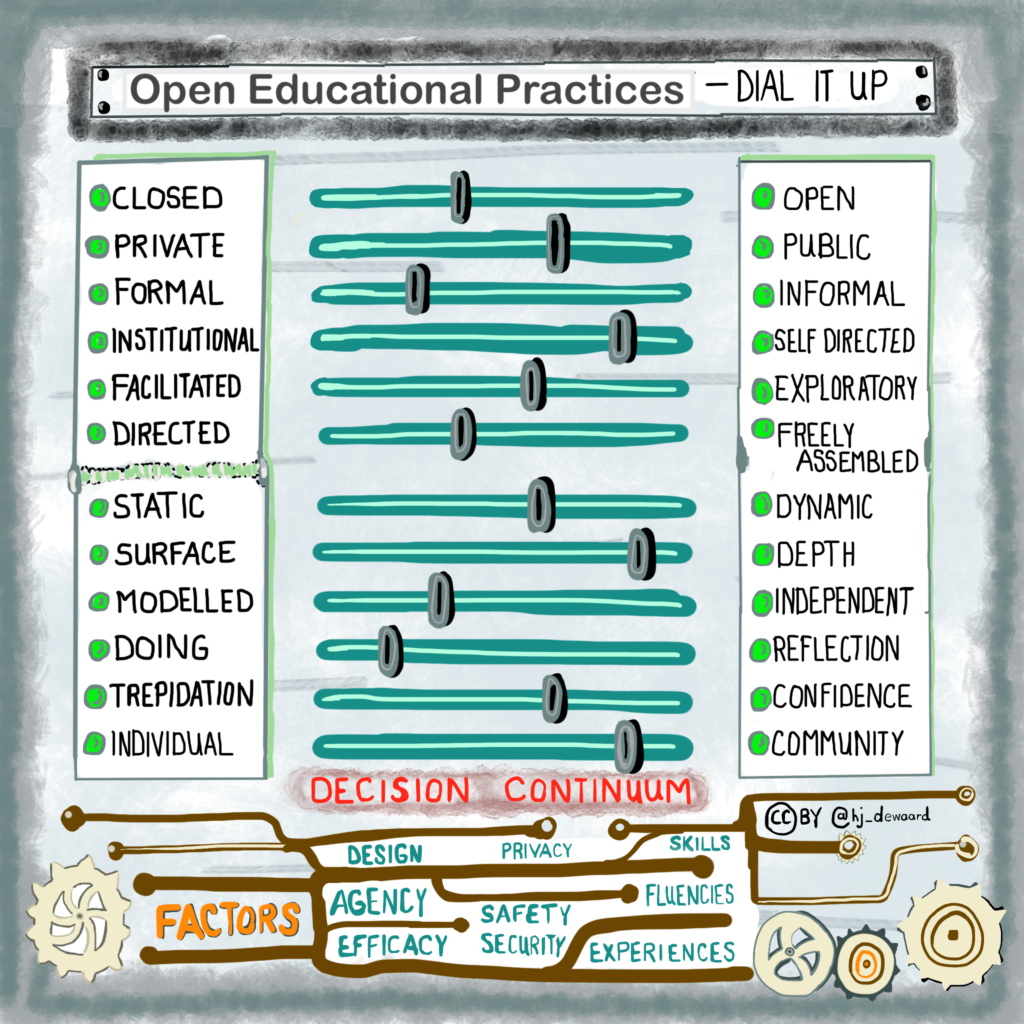

This is as true in open, digital, online, and virtual spaces as it is in a physical classroom context. OEPr is the sum total of an internal ethos, the acts of hospitality, the ways of being “open”, as demonstrated in how a TEd negotiates into open educational spaces, using OER when appropriate, presenting open opportunities, exploring open assessments, while integrating open technologies (Figure 4). For this research, I attempt to construct OEPr within a more holistic framework, re-imagined within both individual and community contexts. Not only does this bring into this conception of OEPr the notion of ubuntu (Geber & Keane, 2017), but also the community of inquiry model envisioned by (Garrison et al., 2001).

One area within this holistic notion of open that is problematic and under researched is the connection between critical digital literacies and OEPr (Cronin, 2017a; Nascimbeni, 2018; Spante et al., 2018; Watt, 2019). It is in this confluence of competing notions about identity and practice, within the field of teacher education, and the OEPr enacted by teacher educators, that I propose to research further. It is here in teacher education that a turn to examining practices is a valuable and critical shift (Koseoglu et al., 2020) that can inform the future of teacher education and the work done.