Working on Working Memory

Week Two: Response to reading prompt

Week Two: Response to reading prompt

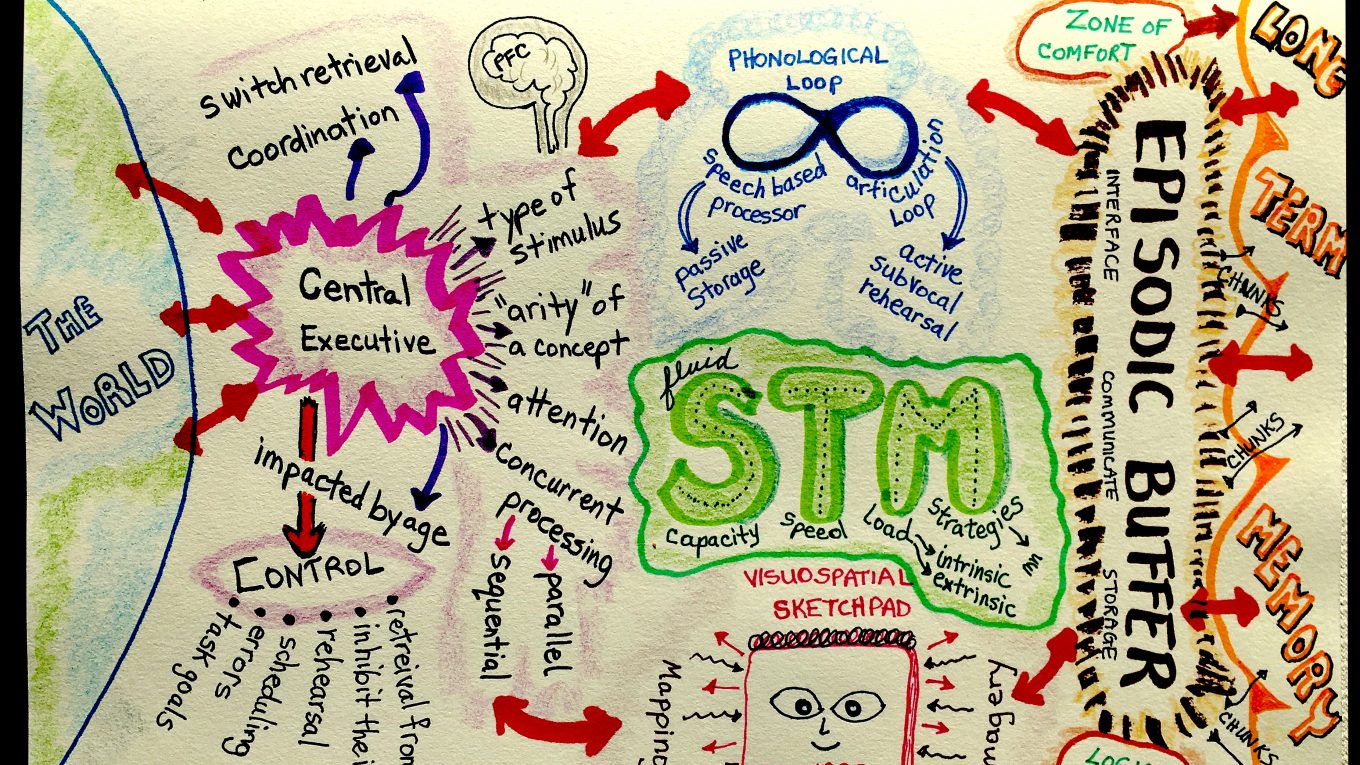

There is no denying the role of emotions in the development of short term memory (STM) also called working memory (WM) (Cowan, 2014; Heathcote, 2016), but there’s more going on than meets the eye. I think it’s important to define the difference, as Martiny, Gleibs, Parks-Stamm, Martiny-Huenger, Froehlich, Harter, & Roth (2015) do, between somatic and cognitive anxieties and how these impact WM. Somatic anxiety is the physiological reaction, more like pre-game jitters, while cognitive anxiety is more deeply ingrained in STM and perhaps similar to imposter syndrome e.g. “who am I to be a great girl goalie?” (Martiny et al, 2015). The model of working memory (Figure 1) may help visualize the processes occurring in this case of positive vs negative stereotype performance issues.

As seen in Martiny et al., the stimulus (i.e. positive talk from the coach) may have short term benefits since it’s focusing on the somatic anxiety (pre-game jitters). This has temporary impact since it’s landing in the central executive compartment of WM (Cowan, 2014), which is where the stimulus (positive words from the coach) and the attention to that stimulus (right before the game starts), is processed and then being filtered through the phonological loop. The coach’s pep talk may be effective in the short term, but unless it moves through the episodic buffer (Cowan, 2014), and becomes stored, it won’t be remembered, thus impacting the long term durability of the positive talk on cognitive anxieties that may be present. Research suggests (Cowan, 2014; Heathcote, 2016; Willingham, 2009) that repetition, chunking, and the duration of the messages, that come from both external (the world, i.e. the coach, mentors in the field) and internal (chunks of information stored in long term memory), impact how they are used by STM in the moment (the game or sporting event). I would suggest that repeated us of positive messaging from role models in the field of endeavour (women in sports or STEM positions), along with a program of positive self-talk, can become part of a working memory training regime, as explored by Cowan (2014), since practice and the potential of self-discovery of new WM processing strategies have potential, with further research study, to improve STM (Cowan, 2014, p. 216).

The implications in the classroom, and efforts to alleviate this negative stereotype threat, particularly for racialized students, is complicated and complex. It’s a problem worth tackling since there are negative social implications if we, as educators, don’t tackle the issues (Delpit, 1998; Ladson-Billings, 1998). But to put this into a stereotype threat framework shifts the focus from an external, cultural perspective, to one of internal, brain based, cognition driven stance – this opens new opportunities for educator action. As I suggested previously, the opportunity to embed instructional strategies that are ‘brain friendly’ and “adjust the materials to the working memory capabilities of the learner” (Cowan, 2014, p. 218) have potential to engage not only the central executive portion of WM, but to enhance the likelihood of activating long term memory. This can be done through active engagement of the episodic buffer of WM, by building logical connections and working within the zone of comfort. With students who experience multiple negative stereotypes in their learning environment, educators can address cognitive development through acceptance of variation in students’ differences with sensitivity, and by engaging students in keeping a diary (Willingham, 2009) to record positive self-talk, motivations, and messages from models or mentors in their field of endeavour.

References

Cowan, N. (2014). Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Education Psychology Review, 26, 197-223.

Delpit, L. (1998). Silenced Dialogue: Power and Pedagogy in Educating Other People’s Children. Harvard Educational Review, 58(3), 280–298.

DeWaard, H. (2018, September 20). Model of working memory. [image]. Retrieved from https://flic.kr/p/2aaxWmY

Heathcote, D. (2016). Working memory and performance limitations. In D. Groome & M. Eysenck (Eds.), An introduction to applied cognitive psychology. New York, New York: Routledge.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1998). Just what is critical race theory and what’s it doing in a nicefield like education? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(1), 7-24. DOI:10.1080/095183998236863

Martiny, S. E., Gleibs, I. H., Parks-Stamm, E. J., Martiny-Huenger, T., Froehlich, L., Harter, A. L., & Roth, J. (2015). Dealing with negative stereotypes in sports: The role of cognitive anxiety when multiple identities are activated in sensorimotor tasks. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 37(4), 379-392.

Willingham, D. (2009). Why don’t students like school? San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.